-

Exhibitions

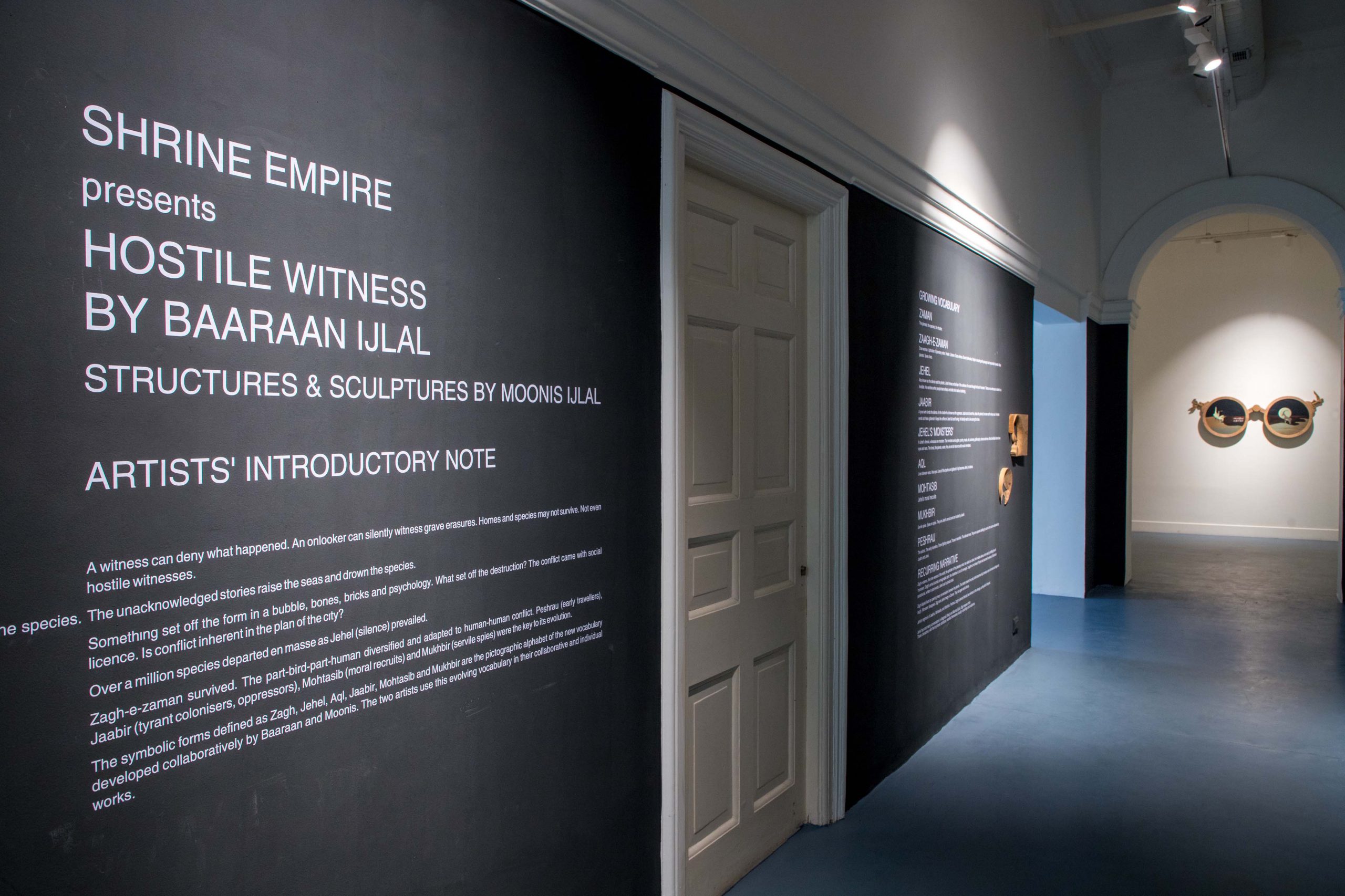

- Hostile Witness by Baaraan Ijlal |

Structures & Sculptures By Moonis Ijlal

- — Baaraan Ijlal

-

![Final Frontier: Jabir in the scramble for status]() Final Frontier: Jabir in the scramble for status

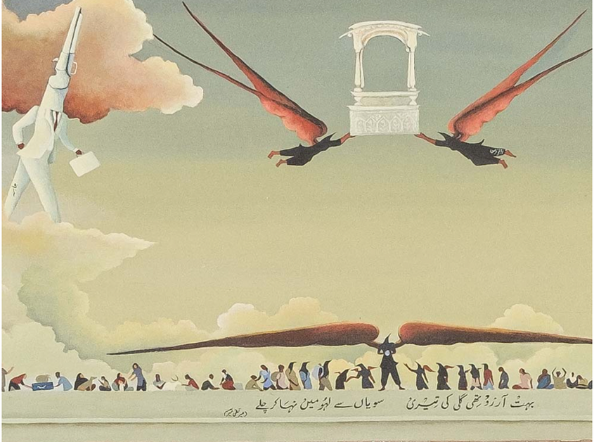

Final Frontier: Jabir in the scramble for status

-

![Final Frontier: Jabir in the scramble for planets]() Final Frontier: Jabir in the scramble for planets

Final Frontier: Jabir in the scramble for planets

-

![Final Frontier: Jabir’s ruinous march from blue to red]() Final Frontier: Jabir’s ruinous march from blue to red

Final Frontier: Jabir’s ruinous march from blue to red

-

![Mohtasib: Moral recruit of Jehel, the invisible lord of fear and silence | Zagh-e-Zaman: The upholder of the planetary order]() Mohtasib: Moral recruit of Jehel, the invisible lord of fear and silence | Zagh-e-Zaman: The upholder of the planetary order

Mohtasib: Moral recruit of Jehel, the invisible lord of fear and silence | Zagh-e-Zaman: The upholder of the planetary order

-

![Final Frontier: Peshrau]() Final Frontier: Peshrau

Final Frontier: Peshrau

-

![Hostile Witness: Diwan-e-Aam, Delhi]() Hostile Witness: Diwan-e-Aam, Delhi

Hostile Witness: Diwan-e-Aam, Delhi

-

![Hostile Witness: Calcutta 7]() Hostile Witness: Calcutta 7

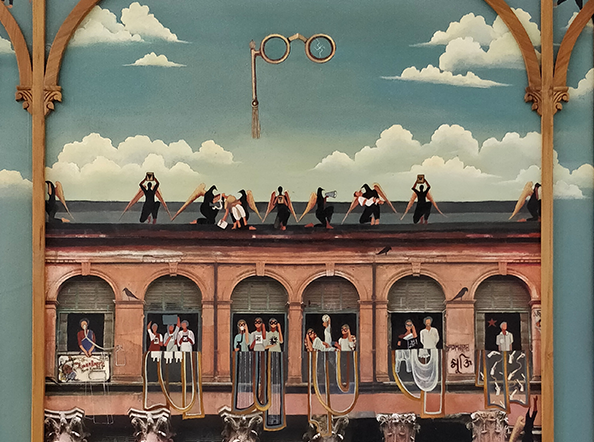

Hostile Witness: Calcutta 7

-

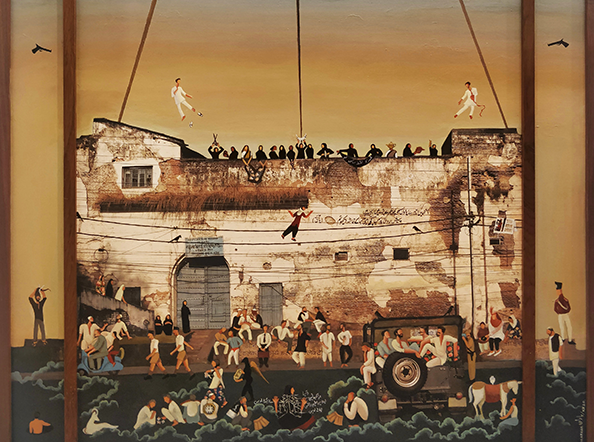

![Hostile Witness: Awadh, Lucknow, Aminabad]() Hostile Witness: Awadh, Lucknow, Aminabad

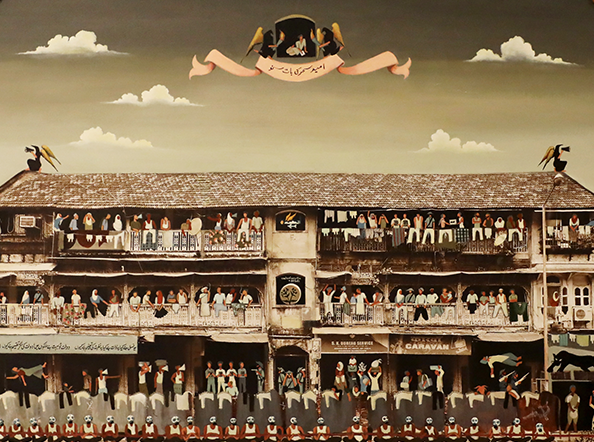

Hostile Witness: Awadh, Lucknow, Aminabad

-

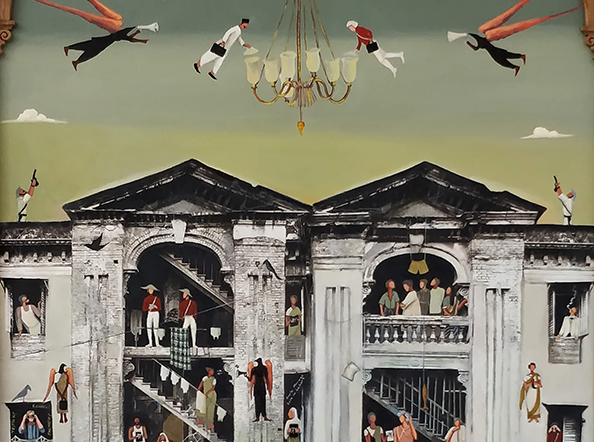

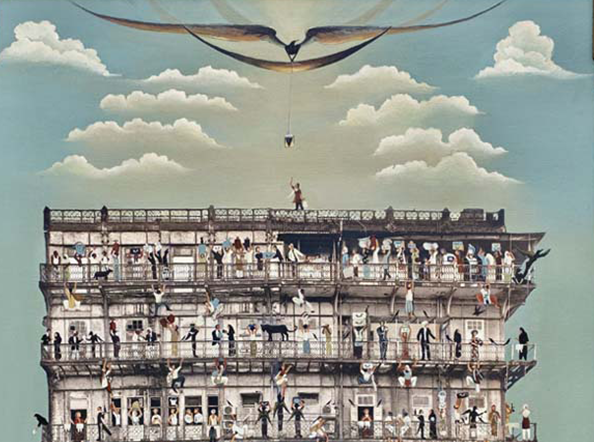

![Hostile Witness: Alexandra Court Calcutta]() Hostile Witness: Alexandra Court Calcutta

Hostile Witness: Alexandra Court Calcutta

-

![Hostile Witness: Arcadia/ Nagpada/ Mumbai/ Bombay]() Hostile Witness: Arcadia/ Nagpada/ Mumbai/ Bombay

Hostile Witness: Arcadia/ Nagpada/ Mumbai/ Bombay

-

![Hostile Witness: Banaras]() Hostile Witness: Banaras

Hostile Witness: Banaras

-

![Hostile Witness: Chowringhee, Calcutta/Kolkata]() Hostile Witness: Chowringhee, Calcutta/Kolkata

Hostile Witness: Chowringhee, Calcutta/Kolkata

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Hostile Witness: Iqbal Maidan, Bhopal]() Hostile Witness: Iqbal Maidan, Bhopal

Hostile Witness: Iqbal Maidan, Bhopal

-

![Hostile Witness: Jer Mahal/Dhobi Talao/Bombay/Mumbai]() Hostile Witness: Jer Mahal/Dhobi Talao/Bombay/Mumbai

Hostile Witness: Jer Mahal/Dhobi Talao/Bombay/Mumbai

-

![Hostile Witness: Esplanade Mansion Watson’s Hotel, Kala Ghoda, Bombay-Mumbai]() Hostile Witness: Esplanade Mansion Watson’s Hotel, Kala Ghoda, Bombay-Mumbai

Hostile Witness: Esplanade Mansion Watson’s Hotel, Kala Ghoda, Bombay-Mumbai

-

![Hostile Witness: Calcutta 6]() Hostile Witness: Calcutta 6

Hostile Witness: Calcutta 6

-

![Hostile Witness: Grant Road, Bombay/Mumbai]() Hostile Witness: Grant Road, Bombay/Mumbai

Hostile Witness: Grant Road, Bombay/Mumbai

-

![Hostile Witness: Parsi Colony, Bombay]() Hostile Witness: Parsi Colony, Bombay

Hostile Witness: Parsi Colony, Bombay

-

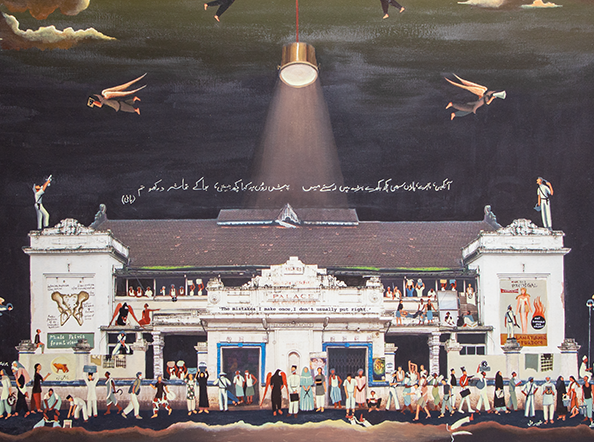

![Hostile Witness: Palace Talkies]() Hostile Witness: Palace Talkies

Hostile Witness: Palace Talkies

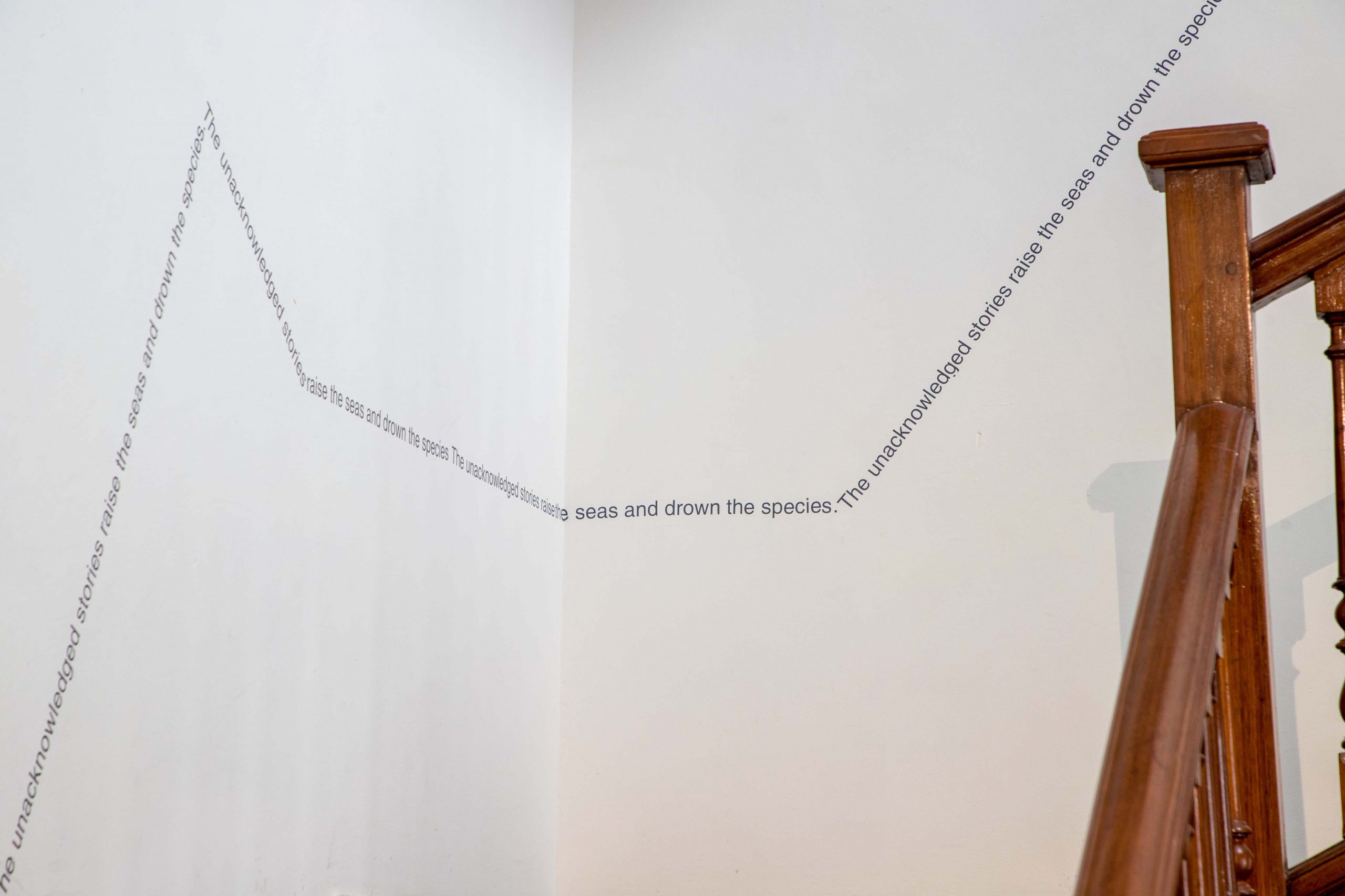

Witness to the Silence Within

When you are living nothing happens. The settings change, people come in and go out, that’s all. There are never any beginnings. Days are tacked on to days without rhyme or reason, it is an endless monotonous addition.

– John Berger1

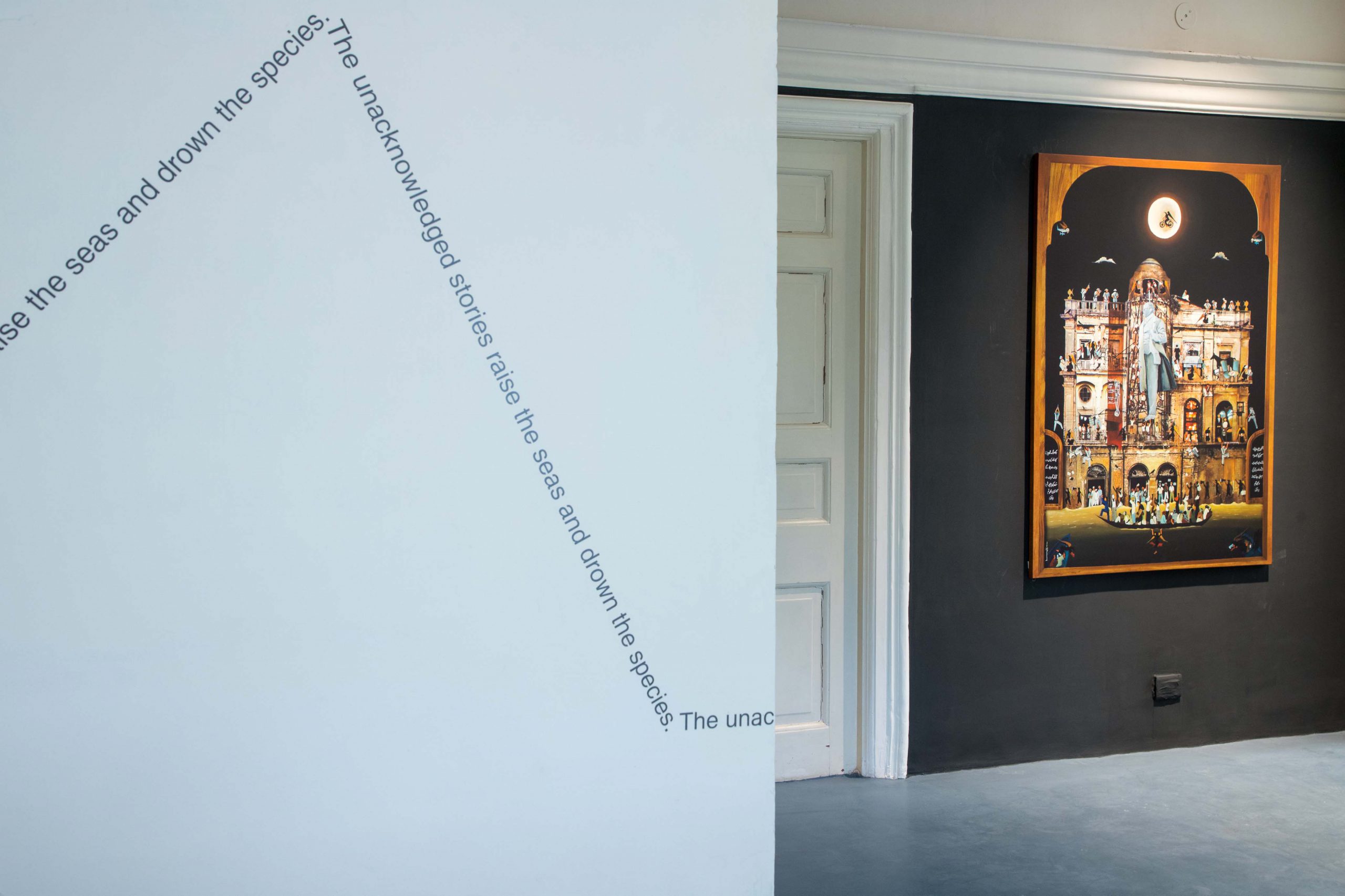

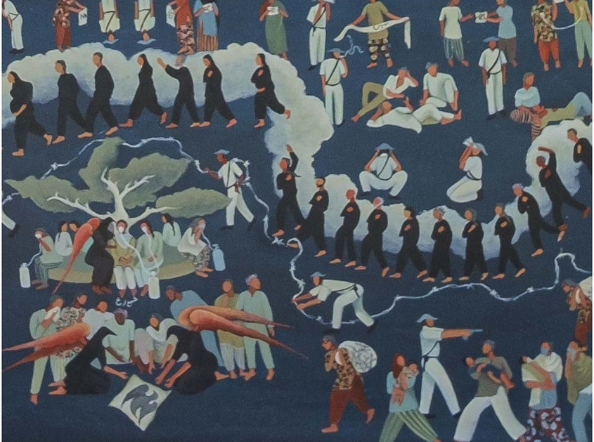

Encountering for the first time the visual tapestries which are Baaraan Ijlal’s works can be a strangely disorienting experience. One reaches around for familiar canons with which to contextualise and articulate one’s responses. Seemingly guileless, they are rich in gentle narrative, but elusive nevertheless in meaning and in layered complexities.

Bachelard speaks of “intimate intensity” and asks if imagination alone is “able to enlarge indefinitely the images of immensity.”2 Ijlal’s works are panoramic in the way they embrace human activity in interconnected spaces humming with movement and intense relationships. One follows these engagements as curiosity builds regarding human stories, their possible meanings, concealments and endings. This vastness can be baffling.

Baaraan Ijlal has recounted her debt to memory – of her ancestral home in Bhopal, and houses experienced in Lucknow and elsewhere. No doubt she dwells on memory, but is it imagined memory?

The philosopher points out that immensity is a category of daydreams, so perhaps the artist in these works has drawn together multiple strands which originated in girlhood memories of home. Nurtured through daydreams, reconstructed, expanded and enriched, they embrace spatial networks which accommodate many disparate lives. Is the artist detached from the past or does she treasure it, rather like pressed flowers between the pages of a book?

Unquestionably, Ijlal welcomes solitude, in which she has contemplated spaces and people who inhabit them. Spaces etched onto lives, filled with her dreams and theirs. Days lived, leaving imprints as inhabitants.

The spaces Baaraan Ijlal so carefully lays out and imagines are simultaneously intense and intimate. They also startle because of the expanse of the canvases, both literally and otherwise, perhaps because one associates such unfoldings with a miniature scale. The traditional miniature in a manuscript allows such meanderings, and hints at inner compulsions in cryptic ways. Baaraan Ijlal is equally oblique in her references and enigmatic juxtapositionings. Figures jostle for attention, ambiguous relationships emerge and meet up in tightly knitted patterns.

To quote Bachelard again, “The two kinds of space, intimate space and exterior space keep encouraging each other as it were in their growth.”3

The intimacy that the artist crafts here is composed of the minutiae of living, delicately thought-out vignettes. Storytelling, being embedded in our visual histories, is often embellished or complemented by text. From the seals of Harappa to the Gandharan frieze, to the temple pichwai, narratives run like rivers – laden with the stuff of life, resplendent with secrets, spilling into spaces, seeping into crevices. One seeks to recall these instances to help unravel what one is looking at.

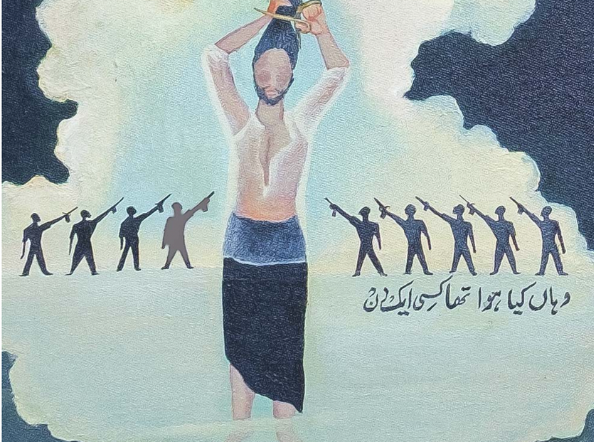

In each of these untitled works (whose locations are noted), Ijlal knits web-like, nuanced and surreal human histories. They move effortlessly in and out of memory scrims, community chronicles, biographical sagas, minor epics. At one level she is deeply immersed in this, but also works at parallel views more remote and dispassionate.

One wonders if the artist’s intent for documentation is rooted in the fear of loss, or whether it is a more ordered ambition to archive and conserve.

Self-tutored in the basics of artmaking, she has navigated its principles with deftness and ease. The thoughtful naivety of imagery is not unsophisticated; the figures are not ciphers, nor the architectural settings passive. The detail of motif, text and symbol are interwoven in seamless ways, and invested with subtle colour values and linear movements.

The elaborate storytelling can make one unmindful of the deployment of the elements used to structure the work. These can seem almost incidental to the artist’s intention. One is in search of more familiar telltale markers of the artist’s presence. The kinship to popular culture in terms of storybook illustrations, small town hoardings, or other instances of visual reportage comes to mind, but such easy categorisations are irrelevant. Popular culture is fast moving and responds to widely felt demands and needs. In Ijlal’s work the mood is one of deep nostalgia coupled with a witty acceptance of human frailty and a sense of making do with what life offers. On a formal level this is attained by the use of scale, motifs and symbols drawn from disparate sources. Like old-fashioned quilts, they insist on their own visual logic.

One ceases to arrive at deductions with which to explain the seductiveness of Baaraan Ijlal’s contemplative, complex musings. They have a way of inviting intimacy into their viewing, and of demanding attention.

Postscript

A fast-paced evolution overtook Baaraan Ijlal’s artmaking as she negotiated a collaboration with her brother, historian and artist Moonis Ijlal. The city and its inhabitants claimed greater immensity in her imaginings, and the political ramifications of the time may have played no small part.

The Hostile Witness (2014–2019) questioned every premise, every cul-de-sac in our histories, their predicaments and their tales of treachery.

Alongside the development of characters in these sagas, which metamorphosed into frames, her installation Change Room is a parallel project of sound recordings replete with stories, jostling with moments of unburdening. As she listened, souls gave up their secrets, and hearts emptied themselves of pain. These fields of pain she drew into herself, almost physically. She says, “My body spills into these large canvases and stands there as a witness.”4

Ijlal comments on these shifting processes that have occurred in the works. “Almost a decade ago, I began looking for conflict inherent in the plan of the city. I dismantled the site, to its bone and psychology. I evolved with the evolving site.”5 She goes on to describe how she paused, listened and reconfigured.

Thus the palimpsest continued to deepen and mature. Transformations occurred as both the artists mulled over the historical horrors and fading traumas in our subcontinent. This intense probing crystallised into symbolic ciphers with distinctive presences and mythological avatars.

The slipping away of these worlds from living memory cried out to be resurrected. Moonis Ijlal inaugurated parallel resonances as frames for the canvases, awakening reverberations in wood. Fresh images culled from the vastness of the canvas were then trapped by wooden binoculars, which stalked meanings anew. The challenge was to reinterpret memory, and recast it into a new story.

Both artists are pledged to weave relationships between their carefully mapped out visual tapestries and the complexities of contemporary turbulences. They negotiate the passages between imperial sagas and familiar tragedies of the everyday of life as we experience it now.

In writing about Zarina Hashmi’s work, Aamir Mufti states, “They recall for us the recurring instances of political violence across the planet in recent decades, from India’s partition in the middle of the twentieth century to massacres in such places as Srebrenica and Jenin in recent years.”6

Baaraan and Moonis Ijlal work from a similar proposition. Ostensibly about the past, these collaborative works assemble archetypes which persist and reappear in our times—Jehel the tyrant, Mohtasib the prosecutor and Peshrau, the symbol of noble hope. While Jehel thrives on the mute, the spectators who concede to compromise, zaagh-e-zaman, the crow woman of the world, does not succumb and persistently resurrects discourse. Manifold and profoundly intriguing, the associations carefully deny complacency to the viewer in the perpetual search for equilibrium. These works, like life itself, are ongoing.

1 Berger, J. A Fortunate Man. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2015.

2 Bachelard, G. The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press, 1969. p.183.

3 Ibid. p.201.

4 Baaraan Ijlal – email to author, Oct 2021.

5 Ibid – email to author.

6 Aamir R. Mufti ‘Zarina Hashmi and the arts of the dispossessed essay in The Migrant’s Time– Rethinking Art History and Diaspora. Ed. Saloni Mathur. Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, distributed by Yale University Press, 2011. p.179.

Through Hostile Witness, artist Baaraan Ijlal is resisting erasure before the seas drown us- Vogue

16th July 2024

Thanksgiving feasts, a crafts bazaar and more for the weekend- Live Mint Lounge

16th July 2024

Of witnessing and listening: Baaraan Ijlal’s art accepts the past to bequeath empathy- STIR World

16th July 2024