-

Exhibitions

- I rescued speed altogether |

Paribartana Mohanty

- — Paribartana Mohanty

The Ethical Dilemmas of Making: Aesthetic Labour in the Age of Demolition

[Paribartana Mohanty and the afterlife of Kathputli Colony]

–Prof. Santhosh Sadanand

Paribartana Mohanty has consistently resisted the stability of medium, genre, and form in his practice. Trained as a painter but refusing to be bound by its modernist legacies, his trajectory – from video essays, performances, installations, to painted forms – has reflected a deeply embodied search for what it means to bear witness to the affective life of the marginalised subject in a violently transforming nation. In his works, the (infra-)structural and the intimate collapse into each other; often evoking not a spectacle of suffering but its residue, its ghostly aftermaths.

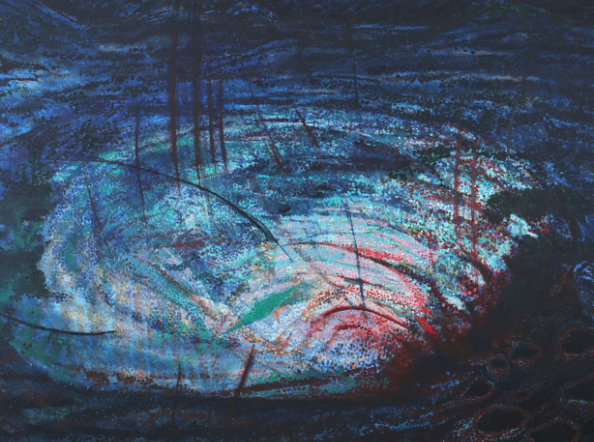

This new painting series marks a deliberate yet dissonant return to the pictorial surface, not as a retreat into formalism, but as a site to reanimate material memory, its scatter, and dismemberment.

From nomadic spectacle to bulldozed silence: Kathputli Colony

Kathputli Colony in West Delhi had been home to hundreds of traditional performers—puppeteers, musicians, magicians, acrobats, a community of artists with long genealogies of itinerant cultural labour. As a living archive of performance traditions, the colony held a paradoxical position: largely invisible to the cultural elite, yet consistently exploited as a symbol of India’s "folk" vitality.

What makes Kathputli Colony unique, and politically volatile, is precisely its status as a symbol of ‘nomadic heritage’, a collective memory not housed in state museums or archival repositories, but performed daily in the unruly geography of the urban peripheries of Delhi. The demolition of the Colony in 2017, under the Public-Private Partnership redevelopment model, marked not just an eviction, but a symbolic burial of that nomadic time – a time that could not be surveyed, taxed, or neatly aestheticized.

Mohanty’s sustained artistic inquiry into the material and symbolic violence of state-led demolitions can be traced across a decade of practice, from his earlier body of work comprising a series of oil paintings and a multi-channel video installation on the demolition of the Hall of Nations at Pragati Maidan (2014–2018) to his current large-format pointillist paintings on the erasure of Kathputli Colony. These two vastly different sites—one an official architectural remnant of Nehruvian internationalism; the other, a living, breathing commons of itinerant performers—may seem to belong to separate registers of history and visibility. Yet, through Mohanty’s practice, they reveal a deeper ideological continuity – of the state's persistent effort to erase heterogeneous temporalities and infrastructures that do not conform to the sanitised futurism of developmental modernity and the insular imagination of nationalism. Mohanty extends these concerns through aesthetic strategies of fragmentation,

displacement, and montage; mirroring the repeated violence inflicted both, on the internationalist imagination and on the urban poor.

The demolition of the Hall of Nations, a modernist pavilion once emblematic of India’s postcolonial aspiration for international fraternity, reflects a broader tendency in the present regime to reorganise public memory. Through practices such as rewriting textbooks, renaming cities, and dismantling architectural traces, this project attempts to streamline the complexities of history into a singular ideological narrative. Mohanty’s multi-channel video installations from this period register the act not as a singular loss, but as a dismantling of memory itself; of layered solidarities, architectural testimony, and everyday internationalism.

This earlier engagement folds into the present work on Kathputli Colony, where the violence is more directly inscribed on the bodies and lifeworlds of the urban poor. Through a radically different formal language – vivid, industrial-hued pointillist paintings – Mohanty registers the epistemic and affective fallout of the demolition of a space that functioned as a nomadic archive of performance, memory, and subsistence. In these works, spatial violence is not simply represented; it is formally restaged. Mohanty’s artistic trajectory thus not only testifies to the recurring logics of dispossession but also refuses to let these erasures slip quietly into history. His practice makes visible what Jacques Rancière terms “the part of those who have no part,” reclaiming, through aesthetic persistence, the disavowed durations, disrupted collectivities, and unassimilated residues that continue to haunt the state’s violent fantasy of order.

Demolitions in cities like Delhi and Mumbai – whether of informal settlements like Kathputli Colony, Madrasi Camp, Dharavi, or Yamuna Pushta – exceed mere spatial clearance. They constitute a forcible imposition of linear, nationalist ‘homogeneity of time’ that disavows other temporalities: those of informal labour, itinerancy, subsistence economies, and performative oral traditions. Kathputli Colony’s demolition, as Mohanty’s paintings painstakingly register, is not just an act of eviction but an epistemic rupture – a loss of world-making practices rooted in embodied knowledge.

Thus, what is being demolished is not just land, but a chronotope; a lived time-space of survival, circulation, and minoritarian joy. The non-statist historical time that these colonies embody disrupts the linear temporality of progress, casting the city not as a neutral container of modern life but as a contested archive of loss and resistance.

Complicating the commons: legal anxiety and spatial dispossession

In the liberal-statist imagination, ‘slums’ are paradoxical spaces; at once criminal and pathetic, invisible and hyper-visible, home to precarious lives but also to ‘encroachers.’ The claim to the commons here is ideologically weaponized. The state and its bourgeois allies do not view the slum as an occupation of shared land, but as a contamination of it.

This logic was most strikingly visible in the judicial framing of the 2025 Bombay High Court judgment upholding Regulation 17(3)(D)(2) of the DCPR 2034. The Court refused to strike down provisions for in-situ rehabilitation of slum dwellers on land officially designated as ‘open space,’ articulating an expansive understanding of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. “A clean city that excludes the poor from access to it cannot be called fair or just,” the court held, reminding the state that the right to life includes not only shelter but shelter with dignity. The court clarified that the provision of housing to the urban poor, particularly those living in informal settlements, is not an act of state generosity but a constitutional obligation grounded in Articles 39 and 21. The bench further noted that “providing formal housing to slum dwellers—within the city and not on its outskirts—is a step towards real equality,” indicating that justice cannot be territorialized only for the privileged.

While the ethical dilemmas posed by ‘slum’ occupations haunt the governmental discourse on the right to life, our critique must not be dimmed by the dull light of practical reason alone. My proposition here is that, contrary to popular belief, what fuels this feverish impulse to demolish is not merely the thirst for land or capital, but a deeper, spectral unease; an anxiety provoked by lives that drift beyond the grammar of control. The urban poor, with their improvised shelters, itinerant rhythms, and fugitive kinships, conjure a time the state cannot measure, cannot master. They are, in Sara Ahmed’s words, affect aliens – presences that trouble the smooth surface of the national imaginary, that carry too much history, too much hope, too much noise. Each demolition is not just a clearing of land; it is a ritual of forgetting, a purge of disobedient time. What is dismantled is not only brick and tarpaulin, but the right to opacity, to dwell otherwise. In these cycles of eviction, the poor are not simply removed; they are rewritten, folded into the language of failure: failed subjects, incomplete citizens, living reminders of a dream the nation cannot quite awaken from. And so they remain – suspended in the long shadow of uncertainty, caught in a present that trembles, a future that never quite arrives.

Demolition as dispossession: aesthetic rupture and temporal politics

The demolitions of sites like Kathputli Colony are rarely isolated acts of urban planning; they are part of a broader logic of erasure that simultaneously dispossesses and dehistoricises. As Mohanty shows in his paintings, the process of demolition collapses the past and future; flattening lived history into debris and projecting a dystopic uniformity as the horizon of development. The demolition of the Colony emerges as both a material act and a symbolic operation – a re-inscription of caste and class hierarchies onto the urban fabric under the guise of ‘world-class’ development. The state’s desire for a ‘clean city’ becomes a desire for a city without memory, without dissent, and without surplus populations that trouble the majoritarian aesthetic order. This is what Jacques Rancière calls the regimented distribution of the sensible – a regime in which the visible, sayable, and audible are policed to produce a seamless consensus around who belongs and who is illegitimate occupants.

The punitive turn in Indian urban governance; what has popularly been dubbed the bulldozer raj, further exacerbates this situation. Under this regime, demolition has been elevated from a bureaucratic procedure to a moral spectacle. Bulldozers are now sent to raze the homes and shops of ‘accused’ individuals; predominantly from Muslim and underprivileged communities, as a form of instant justice, often bypassing due process and despite court orders prohibiting such actions. The bulldozer has become a symbol of majoritarian vengeance disguised as urban governance. Here, demolition is not only a spatial act but a temporal one, short-circuiting the time of law and replacing it with the immediacy of punishment and public spectacle.

In this context, Mohanty’s artworks are not just records of loss; they are counter-temporal gestures. His compositions linger in moments of rubble, repetition, and incompleteness. They reclaim time from the spectacular now of development, drawing us into the slow violence of eviction and the temporal rupture it generates. His work functions akin to what Ariella Azoulay calls an “unshowable archive”; that which refuses closure, refuses healing, and insists on the ongoingness of violence.

The demolition of Kathputli Colony, then, is a symptom of a deeper crisis in the urban imaginary, where development is weaponised against the most vulnerable, where the state abdicates its redistributive obligations, and where memory is made into rubble. Mohanty’s works attempt to inhabit the ruins, forces us to see their life, their temporality, and their refusal to disappear. In doing so, he proposes an aesthetic of resistance; an anti-sublime practice that neither monumentalises nor mourns in the conventional sense, but unsettles. He reminds us that demolition is not the end of a structure, but the beginning of a struggle over visibility, memory, and justice.

Against the expressive self: toward a fraternal ethics of making

The demolition of Kathputli Colony is not only an act of spatial violence; it is also a psychic event, a rupture that unsettles the ethical foundations of artistic practice itself. For artists like Mohanty, who have persistently located themselves within the uneven terrains of political abandonment, marginal survival, and infrastructural erasure, the question is not merely how to respond to such violence, but how to do so without reinscribing the very tropes of affective authenticity, trauma-capital, or voyeuristic empathy that the art market so often craves.

What does it mean to paint after a demolition? Not in the manner of a reportage or catharsis, but as an ethical engagement with the unmaking of possible worlds? Here, to engage aesthetically is not to merely express, but to reorder perception; to interrupt dominant regimes of attention. The artist, then, is not a privileged truth-teller, but a re-distributor of the sensible, capable of creating dissensus – a rupture in the consensual field of what counts as real.

In Mohanty’s case, this rupture is neither declarative nor sentimental. It is a frictional force produced at the site of form – pointillist abstraction, industrial colour schemes, painterly blur, fractured scale. These aesthetic choices resist any easy identification with the politics of witnessing as suffering. They refuse to hand the viewer a digestible meaning. Instead, they install a delay—a lag between affect and cognition, between visibility and recognition, thus enacting what Rancière might call a politics of form.

This positioning is crucial, especially in an era where the artist’s ‘sensitivity’ to the world is often commodified into a brand of authenticity; it is important to resist the overcapitalised trope of the emotionally wounded artist. The problem is not that artists feel too much, but that the structures surrounding art convert these feelings into aesthetic commodities; objects that circulate in elite circuits of taste, detached from the communities whose suffering they ostensibly represent.

How then does one develop a new ethics of fraternal becoming; an aesthetics not premised on affective spectacle or representative empathy, but on shared dispossession? Mohanty’s paintings, in their refusal to finalize meaning, might be seen as material nodes in a fugitive infrastructure; objects that do not belong wholly to the realm of commodity, nor to the state-sponsored grammar of visual documentation, but to a zone of excess, blur, and energetic dissonance.

The pleasure of making, then, need not be renounced in the face of structural violence. Instead, it must be reconfigured; not as a bourgeois indulgence, but as a communitarian act, one that foregrounds shared time, attention, and slowness against the accelerated temporality of destruction. The act of painting, in this view, becomes a form of solidarity-work; not a retreat into aesthetic interiority, but an insistence on being with the aftermaths, the residues, the ruins. It is an aesthetics of endurance, of staying with the trouble long after the news cycle has moved on.

Recuperating aesthetic pleasure: beyond the commodity logic

The historical capture of painting by the commodity-form presents a real impasse. Yet, as Rancière reminds us, the aesthetic regime of art always contains a double movement: it enables art’s autonomy from other forms of life, even as it opens up the possibility of its contamination with them. This tension is not to be resolved, but activated. In Mohanty’s practice, the painterly gesture becomes an act of stubborn insistence. To paint is to persist; not in romantic defiance, but in a quiet, durational refusal of the erasures that urban violence demands. The optical surface of the canvas becomes a battleground where the dust of demolition, the chromatic vibrancy of performance, and the spectral hauntings of community come into contact – not to synthesize, but to coexist in friction. It is in this friction that aesthetic pleasure is recuperated; not as consumption, but as communal sensation, as the shared labour of seeing, of attending, of staying.

In this sense, Mohanty’s paintings are not just about Kathputli Colony. They perform Kathputli’s fugitive logic. They occupy the space between image and event, form and force, affect and evidence. They offer no closure, no catharsis. But they do offer a language; tentative, flickering, affectively disjointed, for a politics of presence in an age of erasure.

One of the most compelling aspects of Mohanty's practice is the notion of eventless witnessing; staying with what is not spectacular, not immediately newsworthy. The ruins, the cracks, the lingering atmospheres after a bulldozer leaves; these become sites of inscription, where artistic labour meets the debris of civic erasure. These are paintings that refuse closure, that retain their fugitive force; a refusal to become part of the white-cube imagination of the beautified city.

This is especially significant in a nation obsessed with image management, where beautification serves as a proxy for governance. Mohanty’s work acts as a counter-visual archive; it shows us that what is repressed—the slum, the ruin, the dust, does not disappear. It lingers in the affective weather of the city.

In this way, Mohanty’s practice resists the entrapment of binaries like beautiful/grotesque or abstract/figurative. What he offers instead is a study in material force, not representation, but intensification. And through this, he reclaims Kathputli not as a lost utopia, but as a living archive of nomadic time: a time that can neither be gridded nor bulldozed.

From scientific optics to affective debris: reorienting pointillism

Nicholas Mirzoeff’s provocative essay “How To Deanaesthetize Monet” offers a compelling critique of how Western visual regimes – particularly Impressionism – were complicit in constructing what he terms White Sight: a racialized mode of seeing that aestheticises domination while disavowing the structural violence underpinning colonial modernity. In Mirzoeff’s reading, the soft optics and ephemeral atmospheres of Monet’s landscapes were not merely formal innovations but visual accompaniments to imperial expansion, spatial enclosure, and the erasure of non-white presences from the pictorial field. White Sight, in this sense, is not simply a matter of representation, but a political sensorium that naturalizes inequality through aesthetic pleasure. This conceptual lens offers a critical opening into rethinking Mohanty’s use of pointillism; not as a revival of impressionist vision, but as an attempt at its reorientation and critique.

Mohanty's return to the dot, the pixel, and the fragment, across his paintings on the demolition of Kathputli Colony, deliberately unsettles the legacy of pointillism as a ‘scientific’ or dispassionate form of visuality. In place of light and leisure, he renders dismemberment, debris, and dislocation. The chromatic intensity and surface density of these works do not coalesce into idyllic harmony, but instead evoke what might be called affective debris: a painterly register of broken lifeworlds, unsettled ground, and incomplete mourning. In this gesture, Mohanty subtly disorients the visual pleasure often associated with Euro-American modernism, opening the optical field to a different kind of engagement; one that implicates the viewer in scenes of ruin, displacement, and unresolved histories.

The debris of demolition, the dust in the air, the affective smog of a razed commons; all are registered through this dispersive materiality. Mohanty’s dots do not resolve into form; they hover in suspension, much like the unresolved afterlives of eviction.

The monumental scale of the paintings of Georges Seurat, the pointillist par excellence, marked a deliberate shift from the intimate scale of Impressionist works to a public-oriented canvas. Its size declared itself as history painting of a new sort, bringing the temporality of bourgeois leisure into the realm of collective address. Mohanty, too, adopts large-scale painting not to monumentalise but to memorialise. The paintings install the unrepresentability of certain kinds of collective loss; the erasure not just of people, but of the memory-worlds they inhabited.

In this, Mohanty’s choice of scale can also be read as a political one. It counters the invisibilisation of subaltern spaces by giving them both a monumental materiality and a fragmented perceptibility. The size of the canvas is not about mastery over the subject, but about staying with the ruined surface; extending the time of attention, resisting the amnesia that accompanies every bulldozer's movement.

Postscript: the ethics of friction

Paribartana Mohanty’s version of pointillism can be considered as a frugal attempt to trigger a redistribution, a dissensual rupture in the optical regime of urban beautification and developmental erasure. These paintings enact such a dissensus not through shock or figural horror, but through the instability of surface, colour, and form. His palette, often composed of fluorescent, synthetic and ‘cheap’ colours, does not represent the ‘slum’; it materialises its volatility. His surfaces are not about ruin; they perform ruin, in its refusal of resolution, in its durational sedimentation of time.

In this sense, his paintings do not so much depict the destruction of Kathputli Colony as they detain it; hold it in a time-loop that refuses narrative closure or visual mastery.

Painting, in Paribartana Mohanty’s hands, is no longer a stable vehicle of either critique or expression. It becomes a fugitive medium, torn between the pleasure of form and the impossibility of justice. It is a practice haunted by its own aesthetic complicity, and yet persistently driven by a desire to remain with the ruin; to register, however obliquely, what remains ungrievable in the eyes of the state.