-

Exhibitions

- Now They Stopped Building Granaries |

Sangita Maity

- — Sangita Maity

-

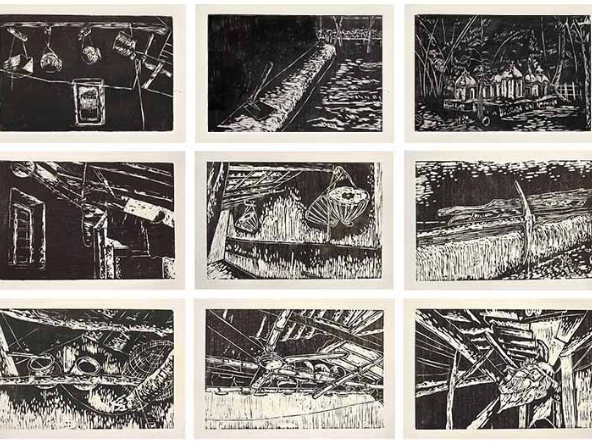

![Dysfunctional tools]() Dysfunctional tools

Dysfunctional tools

-

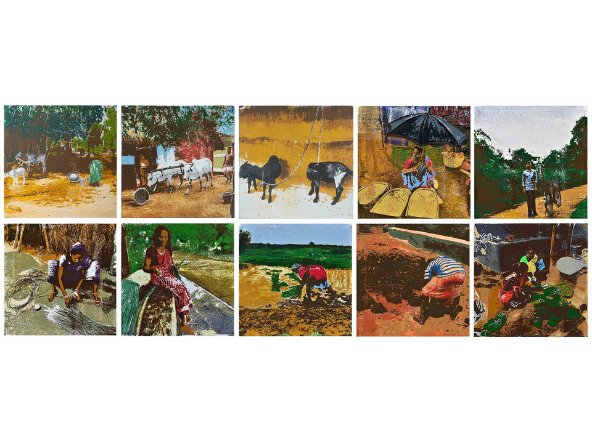

![When they stopped making]() When they stopped making

When they stopped making

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

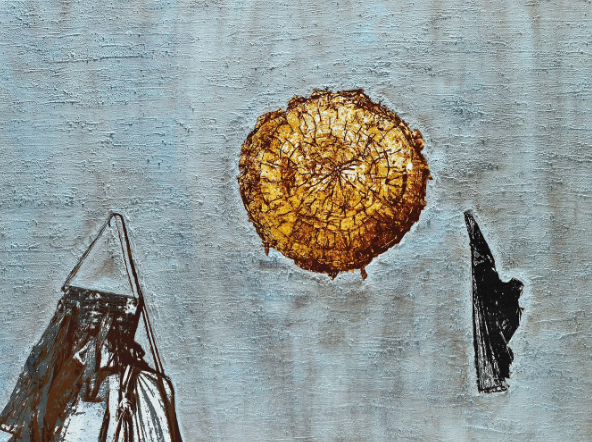

![Industrial Acquisition IV]() Industrial Acquisition IV

Industrial Acquisition IV

-

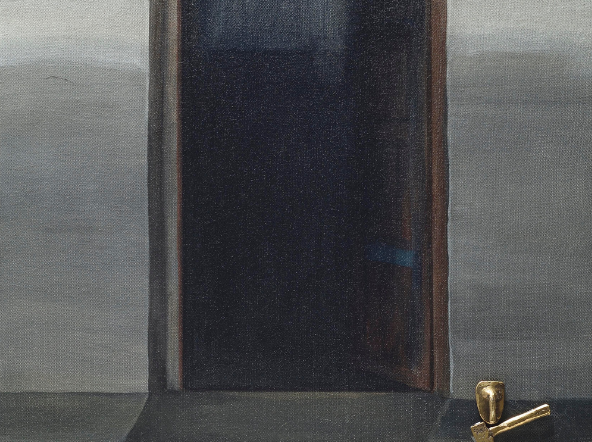

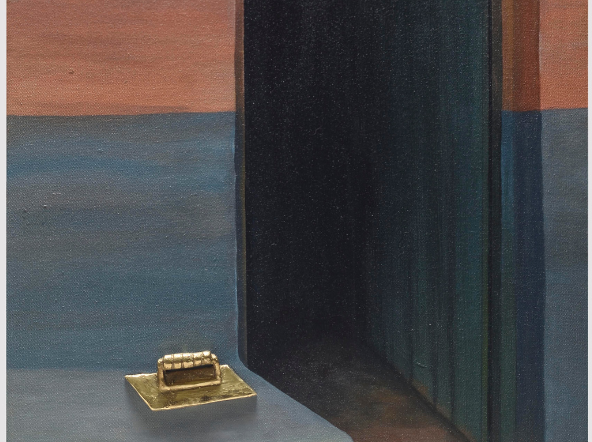

![Dysfunctional tools]() Dysfunctional tools

Dysfunctional tools

-

![Dysfunctional tools]() Dysfunctional tools

Dysfunctional tools

-

![Dysfunctional tools]() Dysfunctional tools

Dysfunctional tools

-

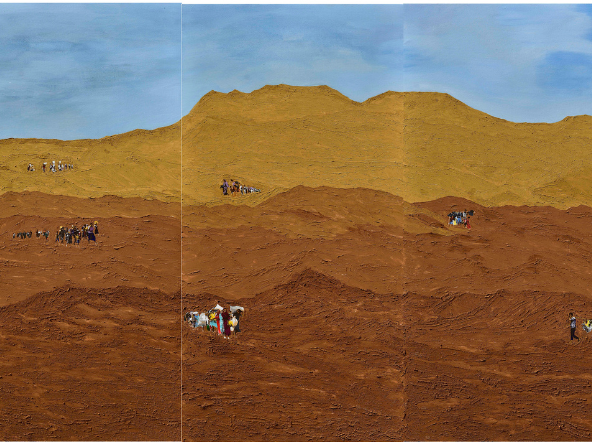

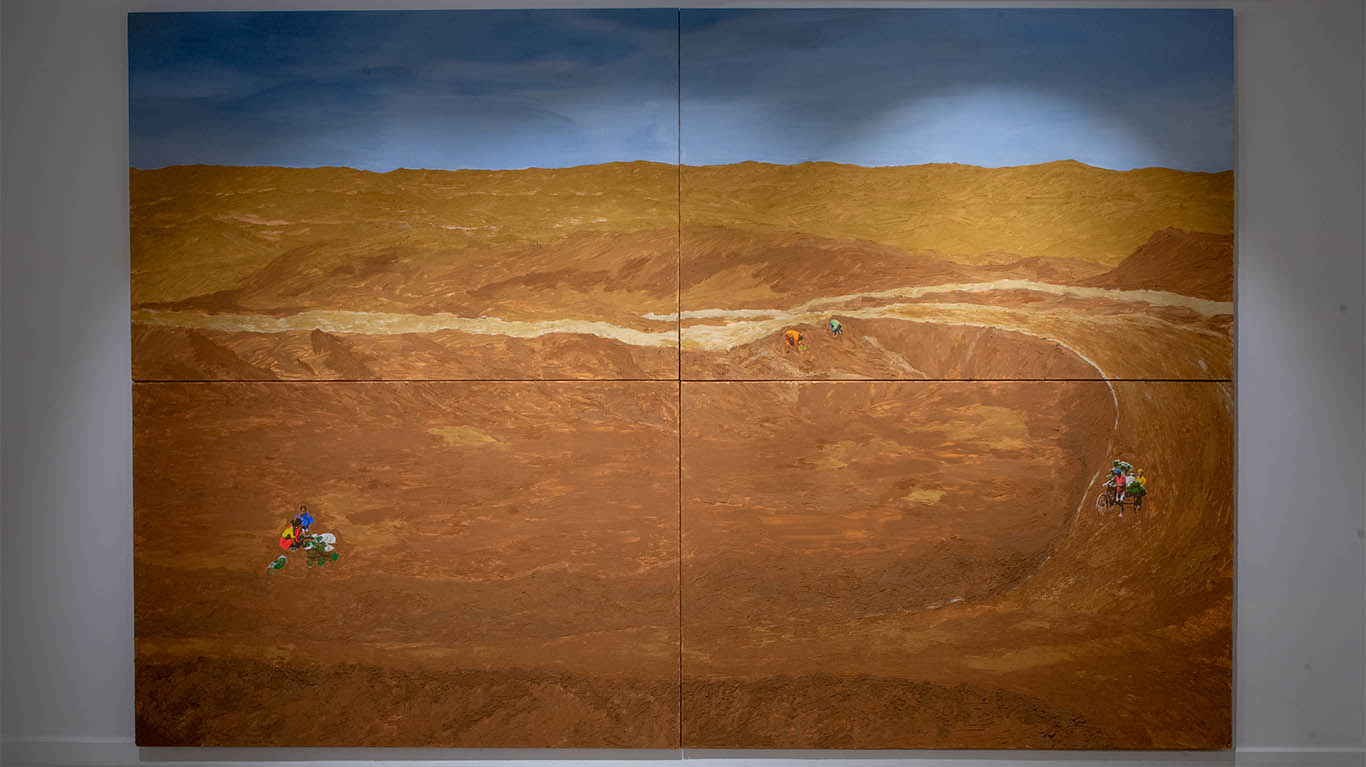

![They are looking for a new village]() They are looking for a new village

They are looking for a new village

-

![Dysfunctional tools]() Dysfunctional tools

Dysfunctional tools

-

![From their tradition]() From their tradition

From their tradition

-

![When they stopped making]() When they stopped making

When they stopped making

-

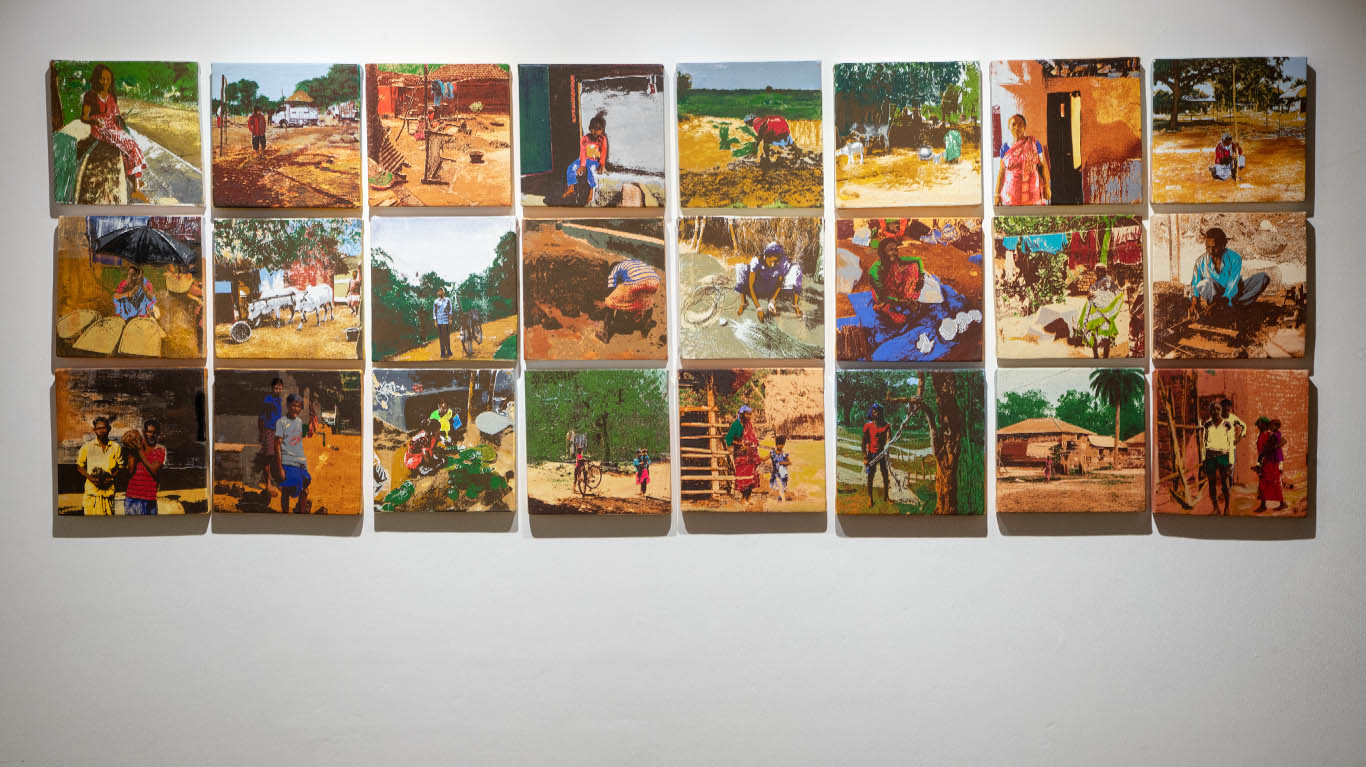

![Wall of traditionss]() Wall of traditionss

Wall of traditionss

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Wall of traditions]() Wall of traditions

Wall of traditions

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

Curatorial Essay

Sangita Maity’s work emerges across two states - of extraction and dispossession. Through fields visits and conversations with the communities of the Choto Nagpur region, the artist untangles complicated histories and conditions of labour, displacement and changing climates. Maity addresses the seething anxiety that envelopes the region head-on. It emerges from accelerated change and a constant abandonment by the state. This dispossession finds its origins in the colonial practices of extraction, has been used by the state over the years to displace people and acquire mineral-rich territories. The only charge and resistance against these oppressive structures is the body that hosts memories and stories, and thereby a people’s history. These bodies have constantly organized, gathered and protested, but the hard reality about models of ‘development’ is that systems are trained to invisibilize and fail us. Maity attempts to do what we must all be – aware, to hold these stories as histories that must challenge large narratives established by the state. Our complicity must be challenged too and we must see, witness. This holding of memory is an act of resistance in itself.

Trained as a printmaker, both material and technique become narrative devices in Maity’s work. For example, she widely uses serigraphy on surfaces prepared with soil or image transfers on metal, materially referencing both, the landscape, and iron ore mined from them. People and objects glisten against the wide surface through a meticulous process of transfer – a scale she uses perhaps to remind us of the abundance of our lands and how it holds us.

In When they stopped making Granaries, Maity builds a relationship between the people that build a structure of care and nourishment – a granary – and a structure of power like a dam, a road built to transport mined goods and warehouses. There is a double violence here – of dispossession and of employment into turning landscapes they come from. Serigraphy again offers both porosity and ‘opacqueness’ – a metaphor (if we read into) to the hollowness and hypnosis of infrastructural promises. The granary then is a space of coming together, building by hand and of caring as a community – a site of resistance, an inheritance and a mode of preservation. For the granary to anchor Maity’s conversations signals both honesty and a strength that emerges from holding faith.

I. Erasure, and to hold memory.

To take away land is to erase its culture. Without a claim to land, a way of life, codes of existence with the natural world, and practices of living with a landscape are immediately severed. Over fertility and practices of preservation, the state has often preferenced “natural resources” held in the bowels of the earth. Once the land is hollowed and the metal and minerals ripped out of its chest, these lands become a playground for industrial opportunities. Sangita Maity’s work emerges against these conditions, through field visits and conversations with people from the Choto Nagpur Plateau spread across the Eastern states of Jharkhand, Bihar, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and West Bengal. The mineral-rich region, home to a number of indigenous communities has emerged as one of the largest extraction sites in post-independence India. Situated between the Indo-Gangetic plain and the Mahanadi river, the coal-rich basin is also mined for mica, bauxite, copper, limestone, and iron ore. Trained as a printmaker, both material and technique become narrative devices in Maity’s work. For example, she widely uses serigraphy on surfaces prepared with soil or image transfers on metal, materially referencing both, the landscape, and iron ore mined from them. People and objects glisten against the wide surface through a meticulous process of transfer – a scale she uses perhaps to remind us of the abundance of our lands and how it holds us.

Maity addresses the seething anxiety that envelopes the region head-on. This dispossession finds its origins in the colonial practices of extraction, and has been used by the state over the years to displace people and acquire mineral-rich territories. With a strong control over laws and policies around indigenous rights, little by means of redressal exists. The only charge, resistance against these oppressive structures is the body that hosts memories and stories, and thereby a people’s history. These bodies have constantly organized, gathered and protested, but the hard reality about models of ‘development’ is that systems are trained to invisibilize and fail us. Maity attempts to do what we must all be – aware, to hold these stories as histories that must challenge large narratives established by the state. Our complicity must be challenged too and we must see, witness. This holding of memory is an act of resistance in itself.

There is a sincerity, a simplicity to Maity's attempt to instill a sense of intimacy and make region in layers of serigraphy as it unfolds across various sites. She leads us to people at work and as they go about their lives in these sacred landscapes and fields that are home – people preparing lands, gathering harvests, shaping tools.

II. Unfavourable Climates.

The harshest implications of the emerging climate crisis, have touched the heart of our already vulnerable forest lands for decades now. Outside of large conversations around the ‘catastrophe’ as peddled by big capitalism and state interests, engineered to pass the onus onto civil populations – in a concerted to clean their conscience – we must remind ourselves that it is the indigenous populations and farmers who have been working to preserve the health of our natural world since time immemorial. At the tipping point, another kind of displacement is not very far from their worlds. Maity has addressed the building of large-scale infrastructural projects including dams in her works over the years concentrating on people of the region, their stories and their employment in these violent concrete productions on their landscapes.

In When they stopped making Granaries, she builds a relationship between the people that build a structure of care and nourishment – a granary – against a structure of power like a dam, a road built to transport mined goods and warehouses. There is a double violence here – of dispossession and of employment into turning landscapes they come from. Serigraphy again offers both porosity and ‘blockages’ – a metaphor (if we read into) to the hollowness of promises and the hypnosis of infrastructure. Her dysfunctional tools on the other hand represent more things – a suspension of ancestral practices and skills; a severance caused by the unavailability of land and of irregular climates; and also of people in a state of stagnation. Conditions made unfavourable by systems. Carved and turned by hand, the implements without handles emerge from Maity’s patience with woodcuts – a precise scratching of surface to carve images. Its visible edges, sharp to the eye, but blunt to work with continue to represent people and their practices in a state of suspension. Labour and migration consistently emerge in the artist’s work, and they are intrinsically tied to the exploitation of land and natural systems.

Distance in Maity’s work could be read as many things as well. Maybe it is a coming to terms with her own position in telling these stories; of positions and privileges. It is also an attempt to depict time and change. In Industrial Acquisition, 2021 women are busy at work in paddy field, knee-deep in the slush while a silhouette of an industrial machine emerges in the distance. She uses the cinematic trope of foregrounding and marking the distance to establish a periphery, a background to also define another kind of distance.

I must return to the granary as a space of coming together, building by hand and of caring as a community – a site of resistance, inheritance and a mode of preservation. For the granary to anchor Maity’s conversations signals both honesty and strength.

-Mario D’Souza