-

Exhibitions

- Shifting Terrains / Altered Realities |

Group Show

- — Anant Joshi

- — Arunkumar HG

- — Kumar Kanti Sen

- — George Martin

- — Dhruvi Acharya

- — Dhruva Mistry

- — Navjot Altaf

- — Pranati Panda

- — Pushpamala N

- — Riyas Komu

- — Manjunath Kamath

Shifting Terrains/Altered Realities

Globalization and global warming are among major factors responsible for a variety of shifts affecting human life. At a societal level, change is a constant. Climate change, natural disasters, terrorism, strife and insurgency, land-grabbing, sectarian and domestic violence: the issues are manifold; the threat to existence alarming. Paradoxically, mind-numbing media static and morbid statistical data has left the urban psyche inured.

Shifting Terrains/Altered Realities, a body of fairly disparate art works from India allows the eye and mind to examine new and recent work by some well known Indian artists who take up a wide range of incidents/events/issues and deeply felt personal concerns to present moments of rupture that may have affected their practice.

In its entirety, the exhibition can be read as a composite commentary, an essentially Indian perspective on the fracture symptomatic of our times, and the still brave human response to it.

Anant Joshi’s water-colors and photographic print of broken/altered/reworked readymade objects, mostly toys of Chinese make, exemplifies an oft used strategy of “deconstruction” and “re-construction” used by the artist. Procuring, altering, assembling and re-arranging the objects in mini tableaux, and then painting or photographing the re-ordered objects is a process that matches cycles of production and consumption seen in fast changing urban environs. Painted in kitschy colors and laid out in rows, like seductive goodies in a sweetmeat shop, these objects, intentionally damaged or dismembered, with tiny decapitated heads, afford a telling statement about the human condition. The artist critiques the global arena with its consumerist economies, where minds are made “comfortably numb” under the daily assault of too many choices.

Arunkumar H G uses cow dung, straw, clay and a used dining table for his evocative assemblage that harks to the disparities that continue to prevail within India’s still largely agrarian economy. A designer with an interest in toy making, Arun Kumar’s partly conceptual, partly sculptural work offers a pertinent comment on issues related to food, production, consumption and disposal. In this instance, a fragile nandi (sacred bull from Indian mythology) fashioned out of straw and cow dung – it occupies pride of place, almost resplendent, on the used dining table – is an ironic cultural symbol that points to issues of class and caste. The same cow dung, used as a purifier or sanitizer in villages, is likely to be viewed as `unclean’ in urban scenarios. Interestingly, the work is far from didactic or moralistic. A lightness of handling and the juxtaposition of natural materials with the readymade, lend the work a playful quality that draws attention to inherent contradictions that exist in Indian society.

The human form is central to noted sculptor Dhruva Mistry’s work. Influenced by classical and modernist sculpture in his formative years, and thereon by international masters, Mistry’s sculpture stands is in a league of its own. Symmetry and form take precedence in his work. Materiality is important, and yet, it does not detract from his long standing desire to reveal the inner being through form, shorn of garment or embellishment. The two works in this exhibition continue in the vein of a recent body of work. The simplicity of form and the lyrical movement of the naked running female figures evoke an awareness of the blitheness of spirit – a celebration of life.

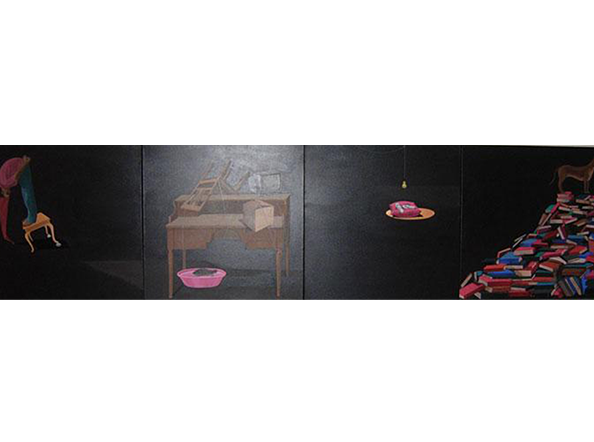

Dhruvi Acharya’s allegorical paintings, detailed and lyrical, reflect the artist’s personal situation – through her protagonist she comments on the psychological tension that arises as she (as representative perhaps of every woman) juggles the demanding/consuming roles of artist, mother, wife, daughter and a woman straddling two world cultures. Intimately rendered, Dhruvi’s work reveals “poetic” moments within the daily tedium of life; she records “…the emotional and intellectual quarrels with the self,” and her own reactions to global crisis. Never overtly political, her world is informed by a subtle and wry humor. She draws the viewer into a space where, as she says, “thoughts are as visible as ‘reality’”. Her paintings are not autobiographical, but based on drawings. (The artist maintains drawing books almost like a daily journal which documents a changing landscape of emotions, observations and experiences.) Influenced by Indian miniatures at one end of the scale and the irreverence of comic books on the other, her works are “layered at a visual and psychological level”. The specific meaning of each image is however incidental, for the artist prefers to recall the universality of human experience.

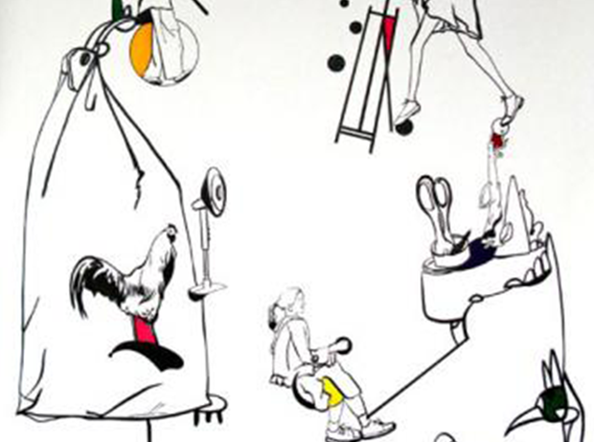

George Martin’s ink and water-color drawing with its Matissean contours could be read as the dance of urban chaos. A painterly exercise between stages of creation, this oddly charming work with its strong contour lines and graphic quality is virtually a register of contemporary life.

Kumar Kanti Sen a designer who holds that “perception is reality” believes that the threat to existence emerges from the process of being in existence itself, given there are subtle, invisible, visible and insidious threats at every level. The two part work with digital imagery of a body image on archival paper and a three dimensional floor piece of a similar image, hark to the individual’s predicament when faced with manipulated realities and unreasonable incidents, including experiences of pain, fear, anger, violence and shock. The artist remains optimistic and hopes that the answers will reveal themselves.

Inspired by the mundane as recorded by the alert observer, Manjunath Kamath’s works capture the immediate through simple narratives and fascinating painterly images. Populated by animals and birds that are occasionally rendered in communion with human figures, his paintings possess a quirky, witty quality and are laced with humor and playful abandon. The small format works call for minute reading – by doing so, one is opening oneself up to possibility of the unsaid revealing itself in serendipitous fashion. Minimalist in some ways, the work thrives on high contrast which the artist creates through the application of flat, luminous background color against which he posits images in a suggestive manner. This conscious juxtaposition creates an interesting balance between the background color field and his chosen narrative elements.

Mithu Sen, in characteristic vein, uses a cropped detail of a photographic image of a classical sculpture of David, shot by her in a museum while in Europe, as the basis of her work. Explicitly titled, Boy toy, the lush close up picture of the sculpted male sexual organ has been embellished further. The artist draws from myth and history to present an ironic commentary. The work is celebratory even as it provides a sharp comment about the politics of power and sexuality. Sen invests the glossy, gold painted image of the inanimate sculpture with a potent sensuality – a characteristic trait of her work. The overtly sexual high gloss image allows her to confront a taboo topic. The ever present spinal column refers to the artist’s own debilitating ailment.

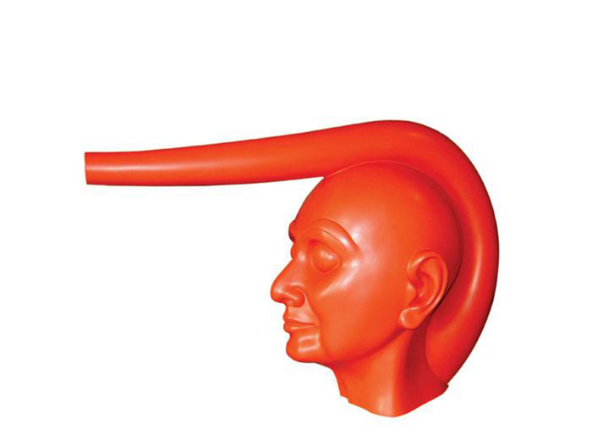

Navjot Altaf who works in the realm of public and community based art, presents a wry, sculptural self-portrait. The third in a series of self portraits that the artist makes when she finds herself amused by something, this work, cast in fiberglass and titled, `To be famous in Lille’, can also be read as a critique of the new consumption patterns of curators in the international cultural arena who choose to present aspects of Indian culture in banal, stereotypical fashion. The elongated trunk like plait is, possibly, a pointed reference to the two oversized elephants that marked the entrance to a famous international event, where the popular and the clichéd drew more crowds than did the contemporary art on display.

Material and pattern come together in Pranati Panda’s mixed media works. Rendered with ink, watercolor, thread, fabric and collage, these beguiling works deal mainly with the dichotomies between the inner and outer world of the female psyche. Drawing from nature – plants, leaves, odd floral forms and fragile insects are among her subjects – she uses images sparingly to create a delicate, occasionally overt symbolism. The florid imagery harks to female sexuality, an exploration of burgeoning identity and the cyclical nature of life.

Pushpamala N’s experimental short film, Paris Autumn created from still, B&W photographs and shot in Paris and India over 2006, is in some ways independent of the brief of this exhibition, in that it was created before and has been sent by the artist as a response to the curatorial axis of this show. Described as a work of fiction in the style of a gothic thriller, the film recounts the story of the artist’s stay in Paris in the autumn of 2005. Strange incidents began happening when she rented a room in one of the oldest streets in the Marais. Soon she realized that she was living in the outhouses of the mansion that had once belonged to Gabrielle d’Estrées, King Henri IV’s favorite, who died, poisoned no doubt, at the age of twenty-six just as she was about to marry the king.

Intrigued by the woman who came to such a tragic end, Pushpamala set off on a quest that began at the Louvre, opposite The Fortune Teller by Caravaggio and continued in the kitsch atmosphere of the Chapelle des Petits-Augustine. We are told that “…the action in the film takes place at various points throughout Paris that Pushpamala, stroller and detective graced with the gift of ubiquity, assembles into a strange map with Haussmannian perspectives, where the Eiffel Tower and cafés follow images of urban violence.” The artist appears “to read the world like a “complex and stratified, open and enigmatic” literary work that she makes up as she weaves her way through a mysterious urban territory where, right down to the flow of the images, we find the “halting” nature of the City according to Benjamin, like a succession of paintings put together with brushstrokes.”

In the past, the artist has taken on the guise of various popular personas and ironic roles in a bid to examine issues of gender, place and history. Her photo-based installations and projections expose cultural and gender stereotyping within the complex terrain of contemporary urban India.

Riyas Komu’s work, taken from a new series titled, Occupation series and painted in quasi- realist mode, reflects the artist’s long standing concern with political and social issues affecting mankind at both, a local and a global level. Focusing on issues related to boundaries and territories that separate even as they bind, Komu’s spare sharp work is one more in memoriam, a touching tribute to the human spirit that loses and yet continues to rise against odds. As a conscious artist he trawls through the onslaught of media static to pick a specific image with particular geographic specificities to present a comment that is universal in its implication.

Sumedh Rajendran presents an assemblage that thrives on the juxtaposition and contrast between materials, readymade objects and ideas. He uses ceramic tiles used in public urinals to form a bent – as if weighed under – body or figure culled from daily life to comment on the human condition. Bathed in an orange glow, the sculpture seems to state that struggle and suffering are an everyday occurrence. The drainpipe and the tin sheet box – it stands in lieu of a space of worship – towards which the figure seems to be headed is a pointer to the artist’s belief that faith too is constricted by conditioning.

Concerned with issues such as ecological damage, violence and atrocities within urban contexts, his sculptural installations possess a slick finish that seduces, even as it leaves the viewer uneasy due to an inherent edginess.