-

Exhibitions

- The People |

Group Show

- — Puja Puri

- — Josh PS

-

![A Muted Existence]() A Muted Existence

A Muted Existence

-

![Adolescence]() Adolescence

Adolescence

-

![Lollipop Rebels in Adventure Playgrounds]() Lollipop Rebels in Adventure Playgrounds

Lollipop Rebels in Adventure Playgrounds

-

![Fall-I]() Fall-I

Fall-I

-

![Fall-II]() Fall-II

Fall-II

-

![It was when We Rise]() It was when We Rise

It was when We Rise

-

![The Way they Landed and Rooted]() The Way they Landed and Rooted

The Way they Landed and Rooted

-

![The Way they Captured and held]() The Way they Captured and held

The Way they Captured and held

-

![The Way they Captured and Protected]() The Way they Captured and Protected

The Way they Captured and Protected

-

![Brick by Brick I construct my Father]() Brick by Brick I construct my Father

Brick by Brick I construct my Father

-

![Father Making the Nation]() Father Making the Nation

Father Making the Nation

-

![Whole World Rove around Us and We are the Centre]() Whole World Rove around Us and We are the Centre

Whole World Rove around Us and We are the Centre

-

![We Are the Witness of Freedom]() We Are the Witness of Freedom

We Are the Witness of Freedom

-

![Weathered Warriors I]() Weathered Warriors I

Weathered Warriors I

-

![Celebration of Innocence]() Celebration of Innocence

Celebration of Innocence

-

![Weathered Warriors II]() Weathered Warriors II

Weathered Warriors II

-

![Children Of War]() Children Of War

Children Of War

-

![When War Intrudes into Table Talk]() When War Intrudes into Table Talk

When War Intrudes into Table Talk

Brick by Brick We Build the People

How do the contemporary artists represent ‘people’ in their works of art? The idea for the show, ‘The People’ stemmed from this basic question. People have been an integral part of visual arts ever since man started making his own image on any available surface. As a representational device with socio-political, cultural and economic connotations, works of art ‘frame’ people as constitutive elements of a society that the artists intend to portray. As far as the aesthetical engagement, vis-à-vis visual arts, is concerned people have a double role to perform. On the one hand people play the constitutive role and on the other they become the actual consumers of this constituted reality. Artists extract and attribute identities for the represented people and in turn the people give identity to the works of art produced by the artists. Art cannot exist without people.

However, people are a nebulous category. Apart from being the consumers of a constituted reality, people do not have any control on the ways in which they are represented in art. Artists, though they belong to this category of people, intentionally step out of prescribed groupings and observe the given categories from a vantage point of aesthetics. Here an artist plays the role of a manipulator of reality. While observing the empirical givens of a society, he could deconstruct it according to the ideals that his art prompts to him. Hence, the representation of people in art is a philosophical discourse, which demands close scrutiny in order to identify the aesthetical and philosophical affinities of the artist.

Generally speaking, in art people are represented as witnesses and victims. People are endowed with a strong gaze with which they scrutinize each and every social occurrences both from the public and private realms. It is not necessary that all these people hold individual identities. They could be a crowd created by a few strokes of paint. The artist, by portraying people within the aesthetic mode, shares the gaze of the people or to put in other words, he borrows the gaze of the people in order to witness the reality that he chooses to portray. As the curator of ‘The People’ show, my intention is to underline this sharing of gaze between the artists and the people.

Throughout the history of art, it is interesting to see, how the artists take special interest in representing people who are victimized by the social realities. The victimizer could the political establishment, totalitarian ideologies, wars, calamities and so on. The roots of the victimized people in representational art should be sought in the history of religious art practices where the suffering of the people is shown as a way to emancipation. But when we come forward in art history, we find the Romantics donning the mantle of social crusaders. They become the unacknowledged legislators of the human kind. Wherever people are victimized the art comes to their rescue. Art gained a new social role with this kind of thinking. Art became a representational device and a political strategy for the resistant ideologies that they insisted art to take sides with the victims by portraying their victimhood and uprising.

There is a curious merger between the gaze of the people as witnesses of the historical process and the victimhood of the people as the subjects of the very same historical process. Twentieth century art majorly upholds this merger by representing people as the sufferers who witness and resist at the same time. Though the celebratory aspects of life have been highlighted in the post-modern and contemporary art, artists still believe that it is their responsibility to function as the gaze of the people. Artists feel this urgency to take sides with the victims and speak for them. Interestingly, art still cannot escape people and their challenging gaze. ‘The People’ is an attempt to find how the young contemporary artists adopt new strategies of representation when they face this inescapable reality, which is called ‘people’. The works of Josh PS and Puja Puri ‘articulate’ the people in this new context and they exemplify how the notions of witnessing and victimhood could be ‘re-presented’ aesthetically, philosophically and art historically.

Josh PS escapes the trap of portraying people as victims of historical process. Instead, he positions himself along with the people around him, as a keen observer of the socio-historical realities. He invests his intellect and emotions in dispassionately observing the history of the colonial past that contributes majorly in organizing the contemporary life. Josh has been working with the images extracted from the colonial era for a long time. His dichromatic paintings and photographs capture the images from the people’s history, which otherwise do not find mention in the mainstream aesthetical or historical discourse.

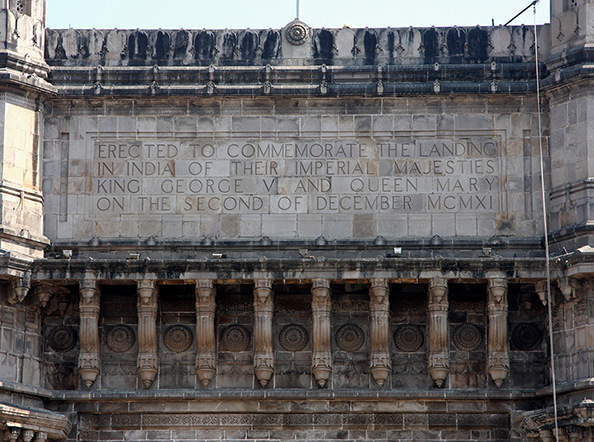

As an artist, Josh PS equates the history of a nation (here India) with the history of its people. For him, it is almost impossible to separate the people from the history of a nation. As I mentioned elsewhere, he deliberately merges the witnessing of/by the people with their erstwhile victimhood. He focuses on the gaze of the people itself and tells the viewers to share the same gaze. One of the photographs titled ‘The Way they Landed and Rooted’ shows the capital portion of the Gate Way of India in Mumbai. Gate Way of India was built as a memorial to register the arrival of Queen Victoria and King George on Indian shores. Now it has become a national monument. People go to its vicinities as tourists and gaze at the magnificent structure. Josh’s intention however, is not touristic. He does not show the complete structure of the Gate Way of India, instead he focuses on the capital inscriptions that herald the arrival of the Queen and the King. By making the people absentees from the scene, Josh articulates how the history of a nation/people changed drastically with this arrival.

It is the same gaze of the witnessing people that we see in Josh’s ‘The Way They Captured and Held’ and ‘The Way They were Protected.’ Josh trains his camera at the monumental sculpture of Queen Victoria placed in front of the Victoria Museum in Calcutta. In the former work, Josh shows the frontal view of the Queen, holding a staff and globe, brining in the symbolic authority of the colonial power over the ‘people’. The latter one shows the same sculpture from behind where the image of a lion is embossed. According to the artist/s (of the sculpture and Josh himself) the empire cannot be thwarted even from behind as there is a lion to protect it. Through these photographs, Josh traces the history of a people who were victimized once, but now liberated and endowed with a strong gaze to look back.

From history, Josh moves to a very private realm to represent people, using his own aesthetical devices. A photograph titled, ‘Father Making the Nation’ shows Josh’s father involved in a quotidian activity of chopping a piece of wood. The man is involved in his act. He is making his home functional and his life meaningful by involving in a very ordinary activity. But the phrase ‘father making the nation’ takes us directly to the history of our freedom struggle, where the whole nation/people were involved in such ordinary activities under the guidance of Mahatma Gandhi, who later became the ‘father of nation’. Josh plays on the pun of the phrase and takes the individual history of a person to the larger history of people. In ‘Brick by Brick I Build My Father’, Josh shows himself (from behind) lifting his child. He could be anybody. But in the process of showing fatherly affection, he actually is rebuilding a history, tracing back a history, participating in a continuum. Josh, from the domestic front represents the whole discourse of family, nation and the historical constructs of these entities.

In two of his photographic works Josh brings in ‘people’ as people; one set from his domestic life and another from his social life. ‘Whole World Roams Around Us and We are the Centre’ shows a family photograph. Here Josh’s father is seen sitting with his sister and the grandchildren stand around them. It is a very private moment. But Josh positions these people as the centre of the world. It is the claim of a nation/people who from their ordinariness claim the authority/freedom to ‘be’ there. In ‘We are the Witnesses of Freedom’, the artist focuses on the notion of witnessing. It is a scene from Delhi’s demolition drive. Josh looks at the people witnessing this demolition, dispassionately, in a sense. The artist actively debates the notions of freedom and witnessing in this work by directly bringing the nebulous category of people in his pictorial frame.

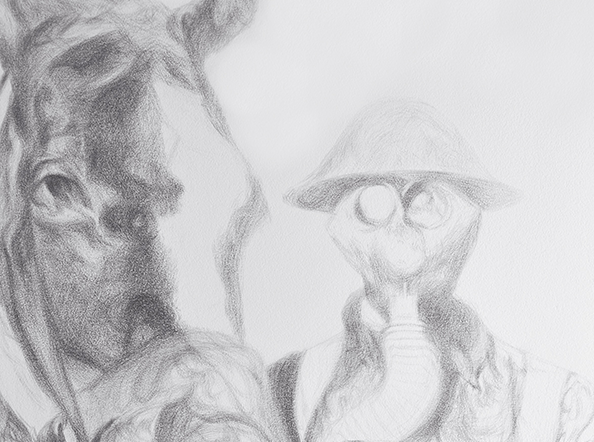

In one of the key paintings done for ‘The People’ show, Josh captures a very important moment from India’s history. On 15th August 1947, India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru gave a speech to the nation from the ramparts of the Red Fort in New Delhi. Josh paints the scene of Nehru speaking, from behind the speaker. But in Josh’s view, we witness not the speaker who is shifted to the left corner of the painting, but we witness the innumerable number of people who have come to witness the historical moment; the birth of a free nation. Who are these people? What happened to them? Where have they come from? Where have they gone? These are the questions that Josh brings forward rather than the magnanimity of Nehru’s speech and presence. In the other two paintings, ‘Fall I’ and ‘Fall II’, Josh produces the counter moments (may be the moments of encounter), where he gives identity to the faceless people as courageous soldiers who fight the terror of colonization. The people are not victims anymore, they, when seen along with the large painting, become fighters (of any country) for a greater cause. The historical distance detaches them from their victimhood and elevates them to the status of martyrs. ‘They are the people,’ the artist says.

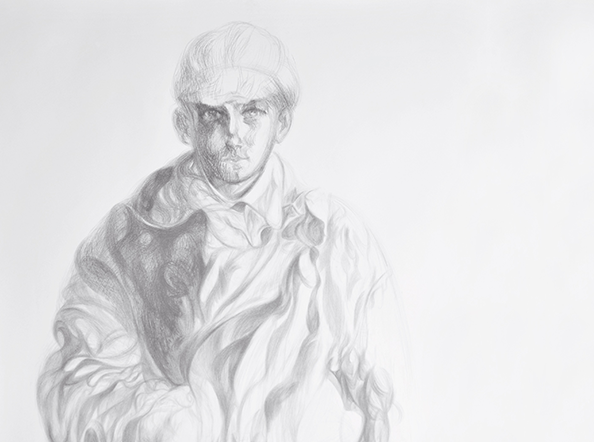

Puja Puri, like Josh, asserts that her ‘people’ are not victims. She is not here to portray people as victims, but as witnesses of their own lives. They, according to the artist, rebuild their own lives in these paintings. In other words, Puja says that by portraying them as individuals and as groups/crowds she imparts them with a new life. For her, history is something that makes the lives of people redundant as history as a literary agency of registering time has the tendency to forget the common people who are outside of the grand narratives. They become a mass, something organic but with no special characteristics. Kings, Queens and political authorities despise people because they believe that people could be manipulated according to the situations. But Puja tries to dispute this fact. She does not look into the particular histories of the nations to locate her people. She traces them in the forgotten photographs that she collects from various sources.

These large scale graphite works (drawings) show the people from different ethnic origins. Puja has a special interest in the portrayal of children. In her view, children carry a micro world with(in) them. However oppressive the situations are, they learn to survive it with phenomenal courage. Puja portrays them in life size drawings with all hagiographic details. The artist feels that these expressions are important because they tell the viewer how these children have already gone through the experience of adulthood well before time. Puja gives emphasize on their garments as she considers these garments as the surrogate representations of the landscapes that these kids have passed through. She deliberately uses graphite as a medium for its tendency to create volumes on the white surfaces.

While looking at Puja’s works, one may tend to ask about the identity of these people. As I mentioned before, Puja’s intention is not to locate them within particular nationalities. For her, people are always in an exodus. It is not just about forced displacement and dislocations. In the contemporary world, people choose to move from one place to another, finding new affinities and affiliations in both geographical and cultural sense. Puja contrasts two historical moments; one, the moment when the people were forced out of their places, and two, when they move on their own will. Her works are the interface of these two moments. She uses these portraits as loaded metaphors. She says that the folded garments carry not only the memories of the lands they left behind but also the impressions of the experiences that they gained while moving from place to place.

Whether portrayed as single figures or as groups, Puja provides them with certain properties. Some of them are seen wearing gas masks. According to the artist, these gas masks or any other properties are used as pictorial devises that would focus the attention of the viewer to a particular point. The question is, why they are given these properties? This probing will lead the viewer to locate these people’s history, within and without the context of representation. Puja deliberately dislodges any attempt from the viewer to see these people as victims of a larger system. Even when the images lead the viewers to identify them within certain historical givens, thanks to their metaphorical insistence, they could be related to any moment from our contemporary times of war and terror.

‘Proximity with the image’ is one of the key aspects of Puja’s works. These images, with their life size appearance create an intimate space for the viewer. The reduction of distance between the viewer and the image results into the interchanging of positions. The viewer ultimately sees himself/herself within the pictorial frame. “The people have been constructed not to make them appear as victims at all. Rather it’s us, the viewers who are perhaps their victims while the heroic models (in various forms of dressing or uniforms) in the work of art stare at us with a peculiar sense of power,” says Puja.

JohnyML

January 2009