-

Exhibitions

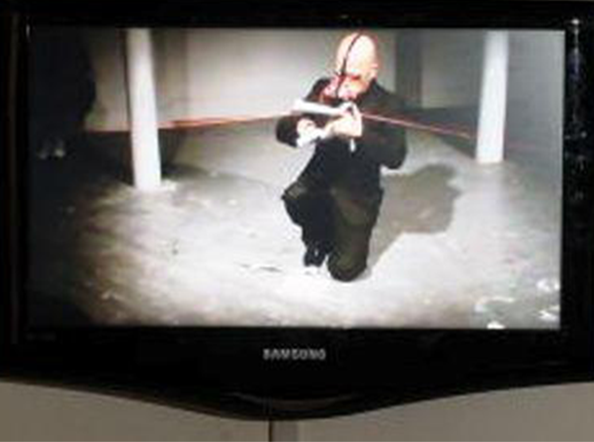

- Whose History Which Stories |

Group Show

- — Atul Bhalla

- — Gim Gwang Cheol

- — Gigi Scaria

- — Changwon Lee

- — Prajakta Palav

- — Siyon Jin

- — Tushar Joag

Lévi- Strauss, observes Catherine Belsey, “wanted to find the common element of all cultures, traceable ultimately to universal structures embedded deep in the human mind. Thus, all myths in the end are transformations of each other…”[ Belsey/Poststructuralism: a very short introduction/Indian edition/Oxford University Press/2002].

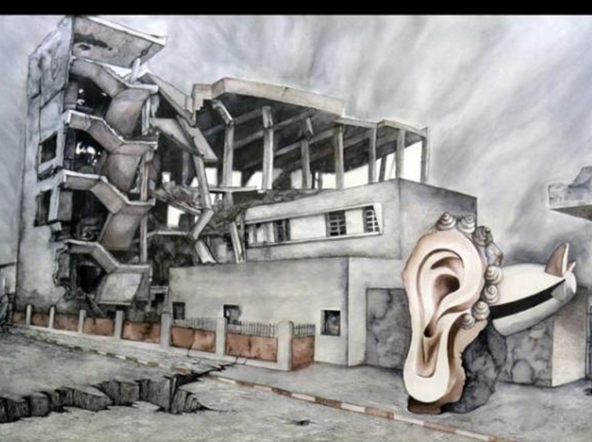

A myth is a powerful weapon for living, existing and reinforcing memory, which means it is a necessity to re-evoke the present so much as the past. We continue to attach ourselves to our past through many a lore. We need to live in one right at the moment. The patterns in the urban situations in India have undergone conspicuous changes since the post-Nehruvian era and the ensuing global economy post 1995, bringing with them, almost surreptitiously, a novel set of crises. Parallel developments unleashed in other parts of the Asian Sub-continent – in this context, South Korea. Our demands turn into dreams and gradually our desires shape up myths in which we constantly delve into. It reflects in our news, adverts, posters, cinema, paintings, toys and through every bit of our urban culture. It is what we aspire to see ourselves in/as.

Myth is also perhaps a reflection of the paradoxes. A couple of such paradoxes in the Korean society revolve around a frantic concern about ‘lost traditions in the face of technology’ or a country which has just transformed itself from repression and parallels to a global order, anticipating about ‘over development’. This co-existence of presence and absence; the past and the future; acceptance and resistance: these dichotomies cannot be ruled out. But they emerge out of a society’s belief in the unknown and the anticipated and finally through its (cultural) practices.

In its use from detergent to cosmetics as; celebration of social rites, rituals and customs such as marriage ceremonies and worships; dreams about cars, apartments and the pride of possession; desire for money and the cult of the epic hero.

The everyday, the mundane, the drab bear an essence of these collective thoughts in which societies continue to thrive. The everyday signifies the collective thoughts in which we think, aspire and take to the values that they assert.

In the urban space where one is especially exposed to an excess of knowledge, information and the resultant fear, it becomes almost imperative to observe how such moorings reflect in contemporary thoughts, or what patterns of thoughts about such myths are revealed by our practices? (For instance the ghost of Communism; the idea of over development or an emphasis and excessive dependence on technology); or is it ideology, rather than myth as Althusser means it? What Barthes terms as ‘myth’ is the same as Althusser calls ‘ideology’ but in the latter case it has a Marxist allegiance.

The confusion between these two terms ‘mythology’ and ‘ideology’ has been solved by Anthropology the key concern or topic of which is – culture. Belsey observes: “That signifier (culture) is not without its problem, too, of course, but it has the effect of implicating us all in the common practices of our society, which are neither true or false but carry meanings and values we may not have chosen consciously.”

Myth is equivocal. We often take myths for fictions, but the purpose of myths is far from being entertainment. They are the origins of things. They explain the cultures that subscribe to them.

This show aims at identifying and addressing those elements that emerge from our cultural and emotional fringes, the discovery and the ‘otherness’ and at the same time portraying the national psyche.

-Oindrilla Maity