-

Exhibitions

- दूर-दराज़ (Dūr-darāz) |

Solo show

- — Awdhesh Tamrakar

दूर-दराज़ (Dūr-darāz)

If you are reading this, you have already pronounced this word in your head. Say it out loud. How does it roll off your tongue?

Now try,

ठठेरा (Ṭhaṭherā)

and,

मठार (Maṭhār)

What is the sound that these make?

Maṭhār is the repetitive sound of metal striking metal—once heard so often in Awdhesh Tamrakar’s community of Ṭhaṭherās from Shahgarh in Madhya Pradesh, known for their brass and copper utensil-making. In recent times, however, this hammering sound has grown so dūr-darāz or distant that it is rarely heard as the younger generation of Ṭhaṭherās seek out different career paths and better socio-economic prospects.

How do you measure distance by sound?

Can pictures hear?

Does metal hold the memory of the sound of its beating?

***

Now say,

ताम्रकार (Tāmrakār).

Awdhesh’s surname literally means craftsperson of copper. Material, then, does not form the crux of his practice simply for aesthetic or artistic reasons, but is an identity marker of his family, community, and place of belonging. Material is political.

The Ṭhaṭherās’ iconic craft of brass, copper, and its alloys, is currently in a state of decline, having to compete with cheaper metals like aluminium and steel in an economy of mass-manufactured goods.

It is through material, therefore, that Awdhesh traces his roots back to a place called Pancham Nagar in Madhya Pradesh—once home to the Shahgarh Ṭhaṭherās but now lies desolate with only some ruins of a fort wall left. To him, a native landscape in decay or a practice in decline can mean the same thing for the Ṭhaṭherā identity.

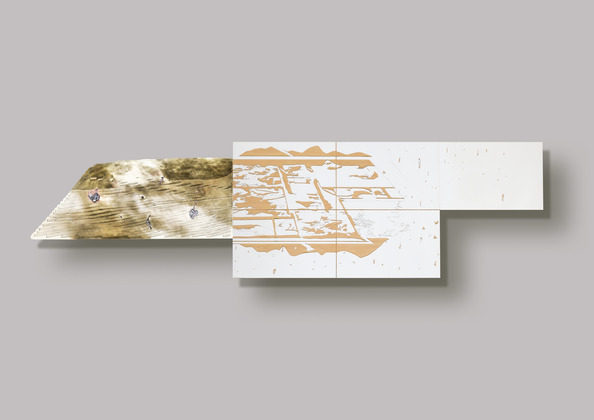

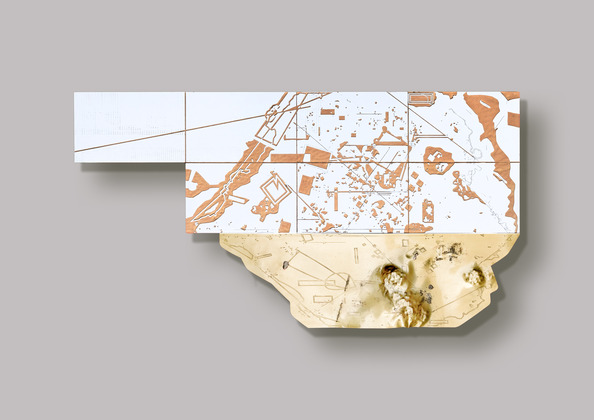

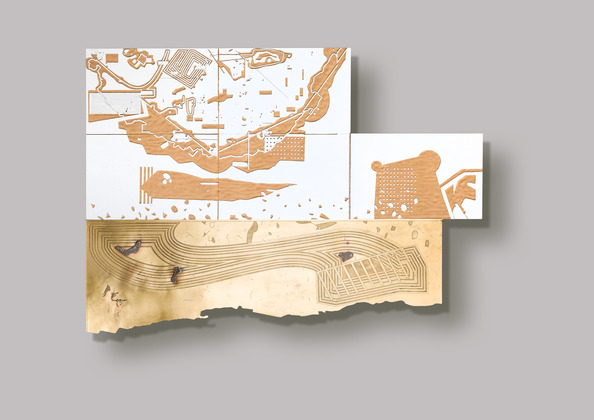

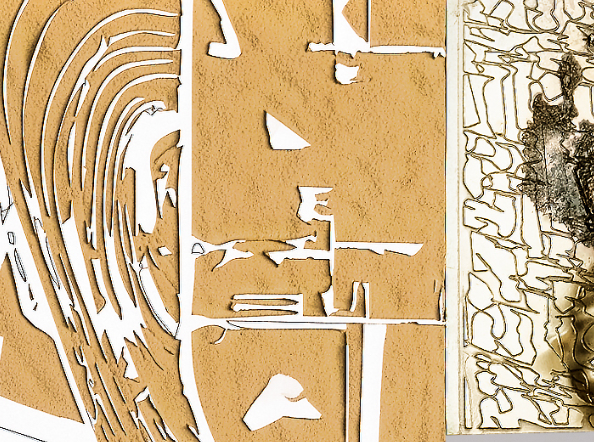

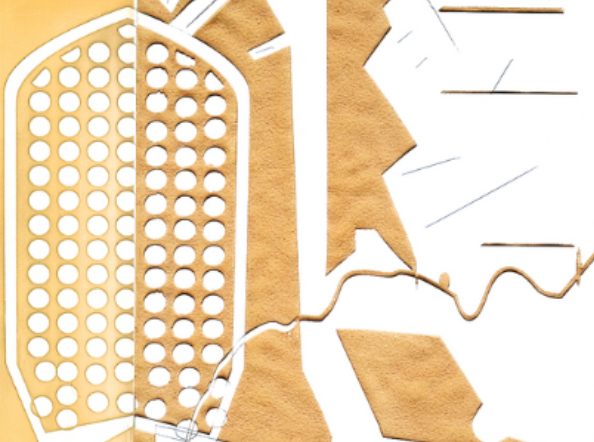

And so, Awdhesh sandblasts and acid-etches Pancham Nagar’s topography into ceramic tiles and brass like a denudation. But the lines are clean and the surface, shiny, like the industrial products that have been sustaining the Ṭhaṭherās economically for years.

***

Awdhesh unearths his heritage—so dūr-darāz in time—from his family archives and local oral histories. It is this memory, recovered in fragments, that he sculpts into fragmented pieces of land mass from recycled paper-pulp in Muted Ground, harkening to a time when Pancham Nagar was known for its paper board (gaṭṭā) factory as well as its metalsmiths.

But don’t mistake his deployment of landscape for nostalgia as it is not a longing for the past. It functions rather, as a place-holder for the present discourse on the dis-enfranchised and the forgotten; It is to articulate loss without lament.

***

Can the maṭhār sound be captured in a picture?

Awdhesh attempts this—not so much to preserve as much as to salvage—by recreating the aesthetics of crumpled photographs from his father’s photo-studio in Pital-Khana, literally meaning a brass workshop. His deliberate mutilation of the surface and the terrain-like undulation of the creased paper denies the viewer an easy view for there are no easy answers here.

As we vaguely make out hands working the metal in some of these works, we wonder if they would one day become as abandoned as Pancham Nagar’s ruins.

What would this mean in the coming years, when children are taught to say,

‘ठ’ से ‘ठठेरा’ (Ṭh se Ṭhaṭherā)?

– Text by Priyanka D’Souza