-

Exhibitions

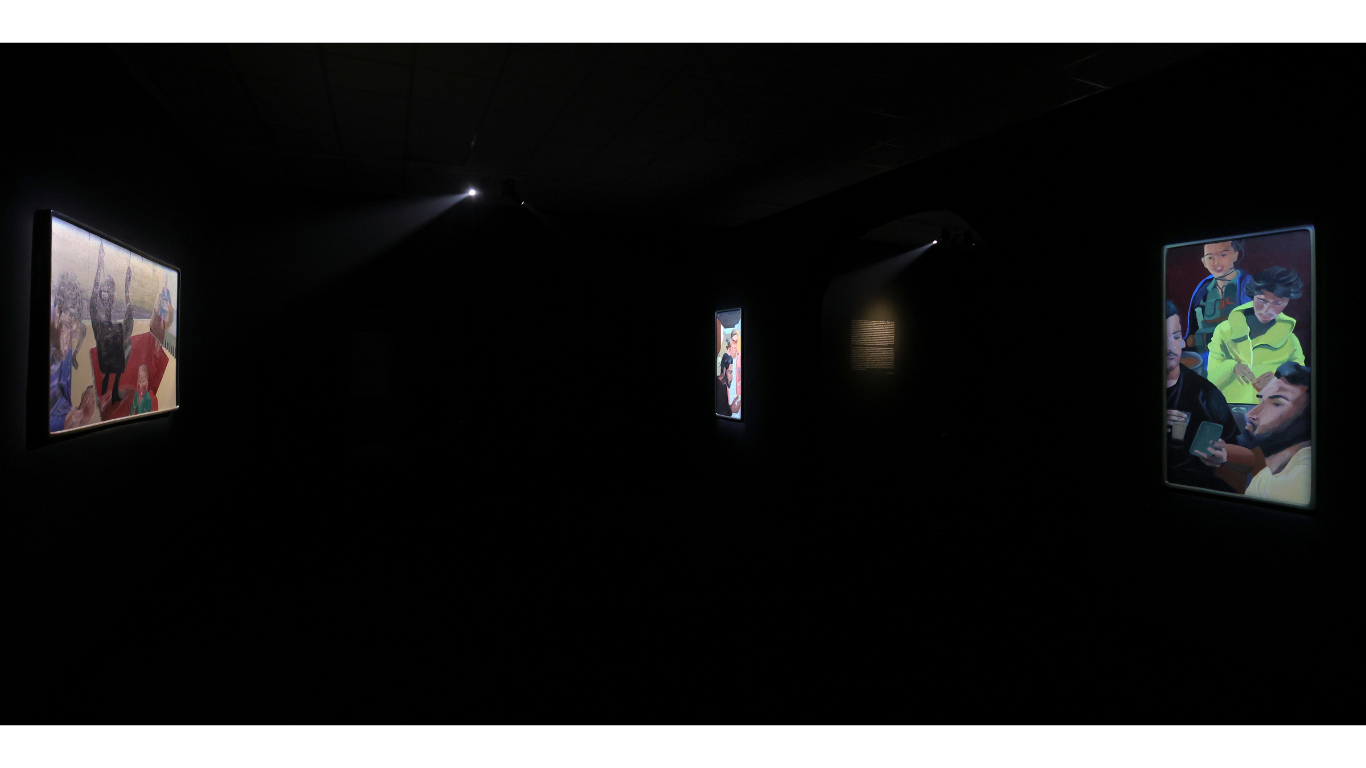

- Lie Machine |

Solo Show

- — Moonis Ijlal

-

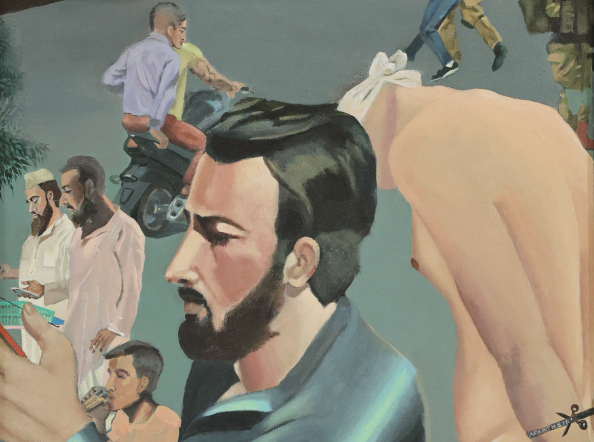

![There’s ice cream for everyone]() There’s ice cream for everyone

There’s ice cream for everyone

-

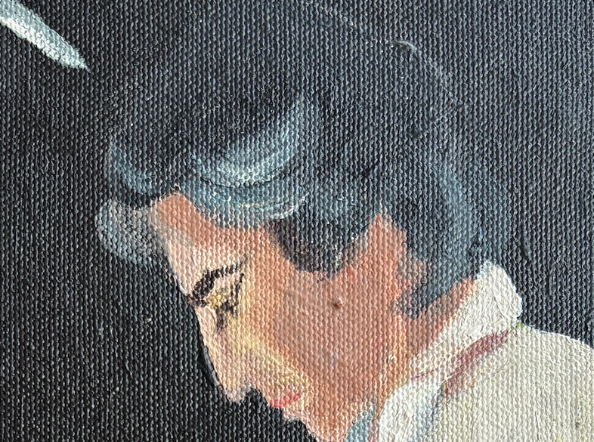

![Mom I know you are proud: She sleeps with the lights on]() Mom I know you are proud: She sleeps with the lights on

Mom I know you are proud: She sleeps with the lights on

-

![You don’t even have the language to describe what is happening to you]() You don’t even have the language to describe what is happening to you

You don’t even have the language to describe what is happening to you

-

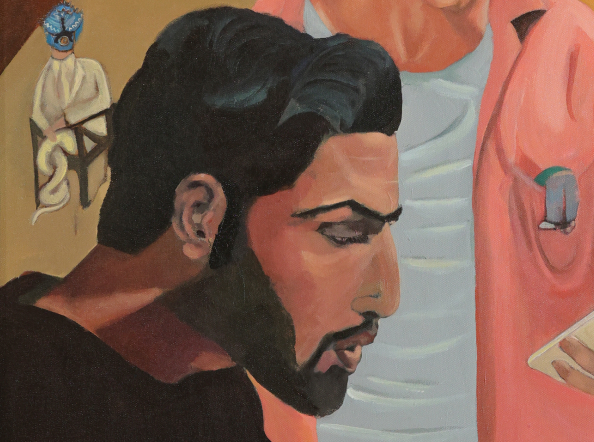

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![Untitled]() Untitled

Untitled

-

![3 am snack: war and workers do not sleep]() 3 am snack: war and workers do not sleep

3 am snack: war and workers do not sleep

-

![Aaj ka gham jo hai, zindagi ke bhare gulsitan se khafa]() Aaj ka gham jo hai, zindagi ke bhare gulsitan se khafa

Aaj ka gham jo hai, zindagi ke bhare gulsitan se khafa

-

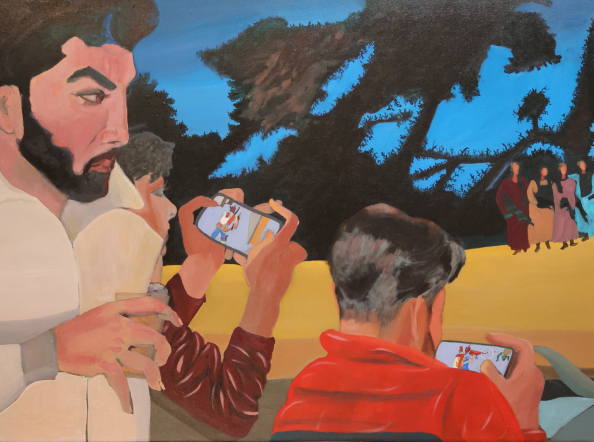

![2 am: Free fire wins of bright clothes]() 2 am: Free fire wins of bright clothes

2 am: Free fire wins of bright clothes

-

![I’ll fix ammi’s table, bada kaam batao]() I’ll fix ammi’s table, bada kaam batao

I’ll fix ammi’s table, bada kaam batao

-

![4 am Tea]() 4 am Tea

4 am Tea

-

![8 pm traffic jam]() 8 pm traffic jam

8 pm traffic jam

-

![At least faux flowers last longer]() At least faux flowers last longer

At least faux flowers last longer

-

![Joystick and the spoils spilling out: Paris on a holiday]() Joystick and the spoils spilling out: Paris on a holiday

Joystick and the spoils spilling out: Paris on a holiday

…zakhmi hain kaan

apni avaz kaise sunun.

—Kaifi Azmi

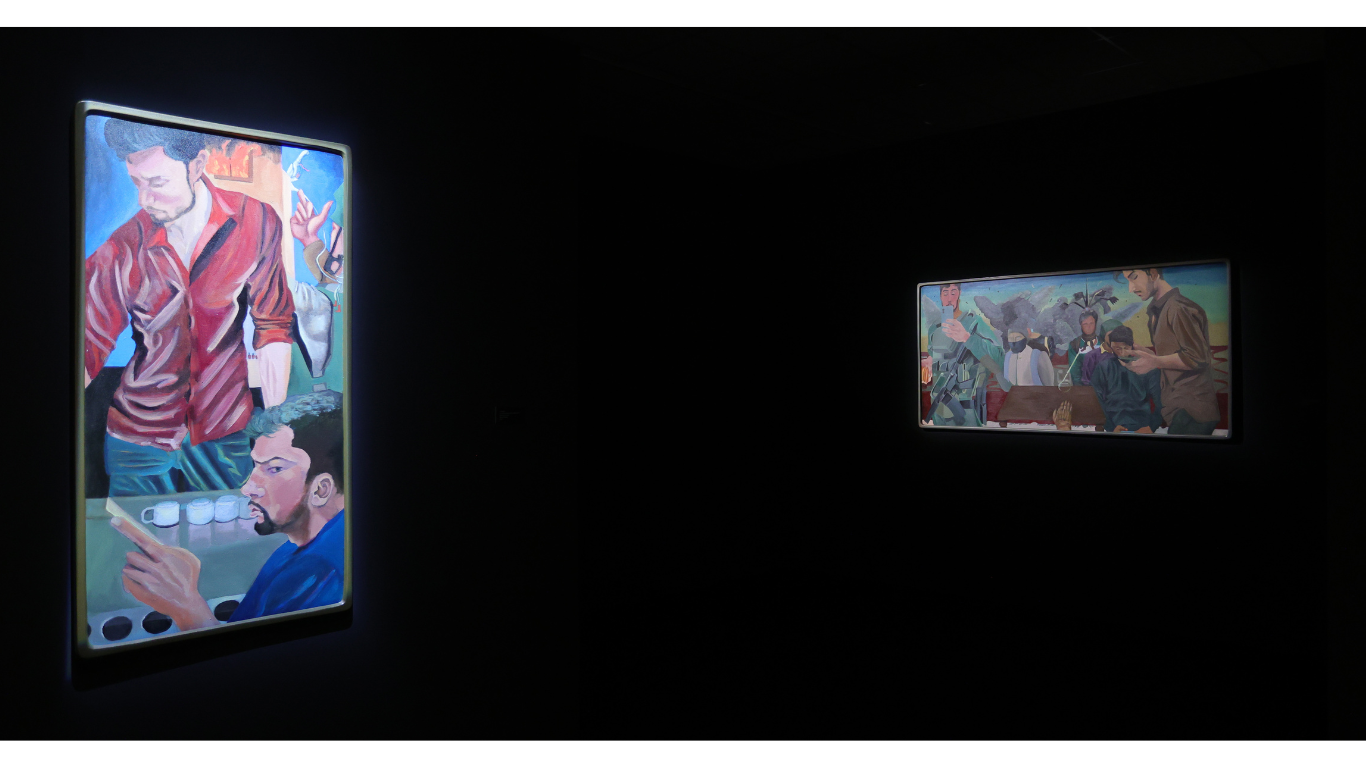

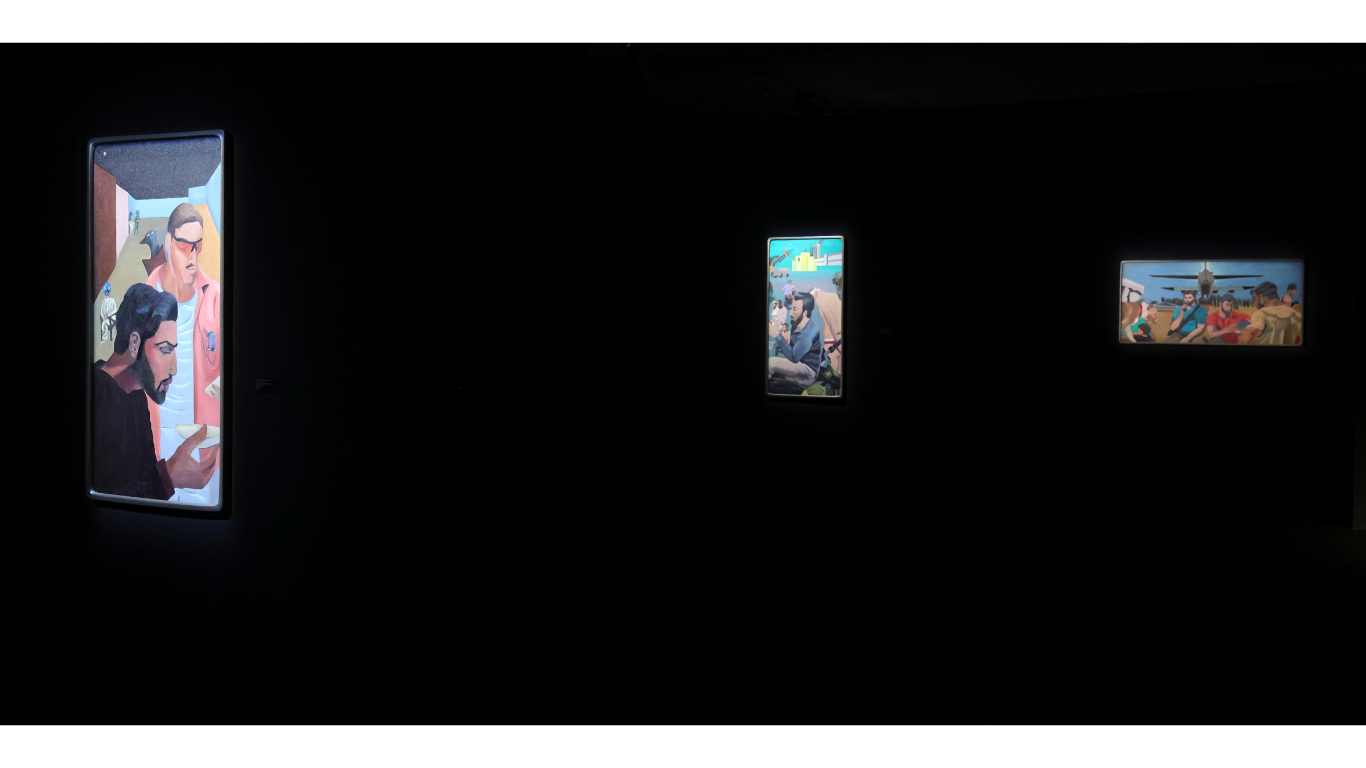

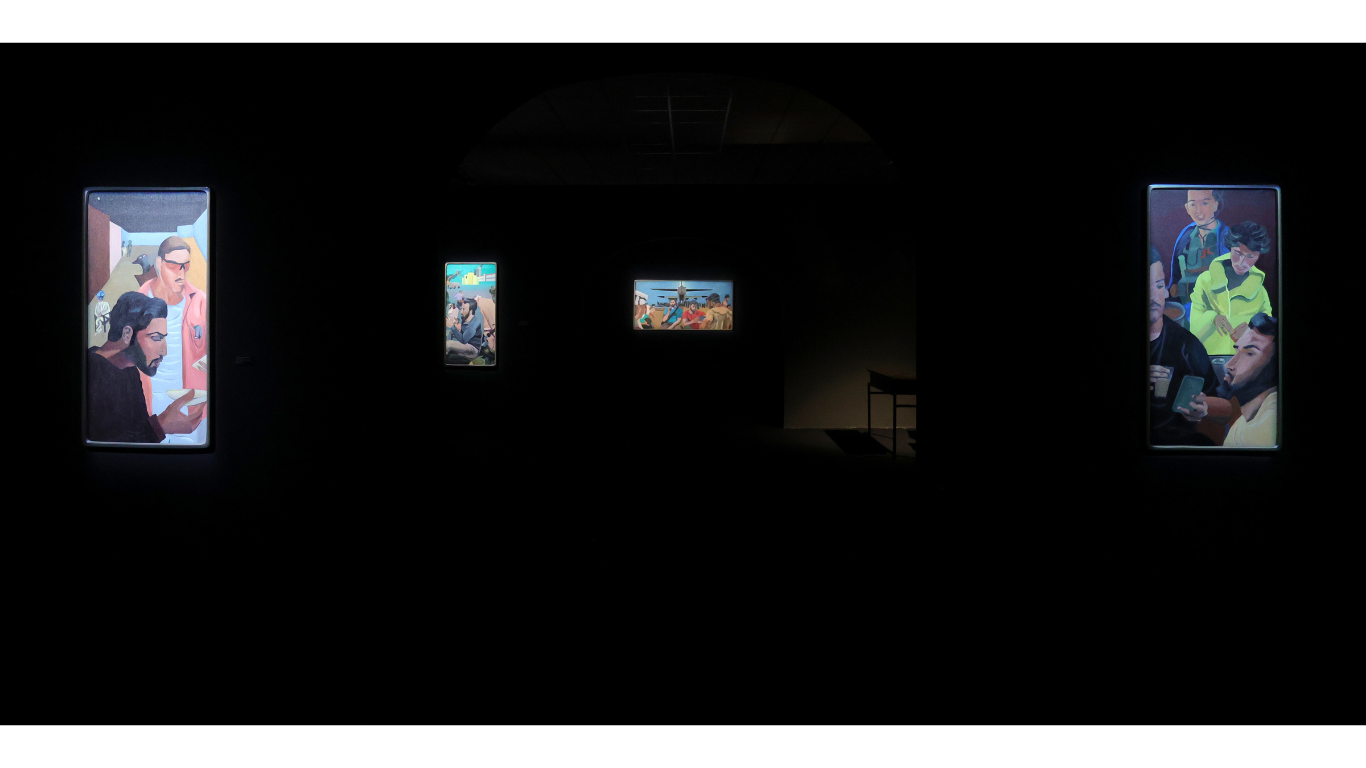

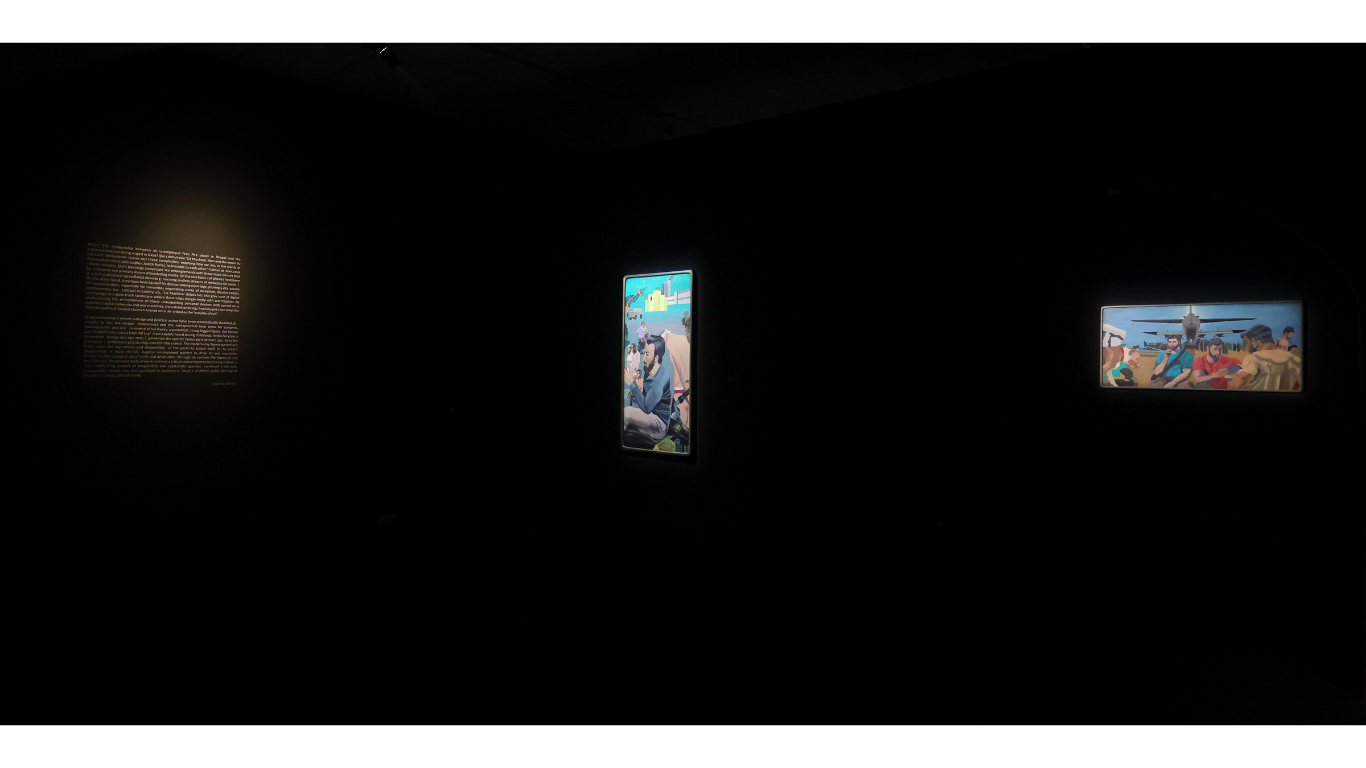

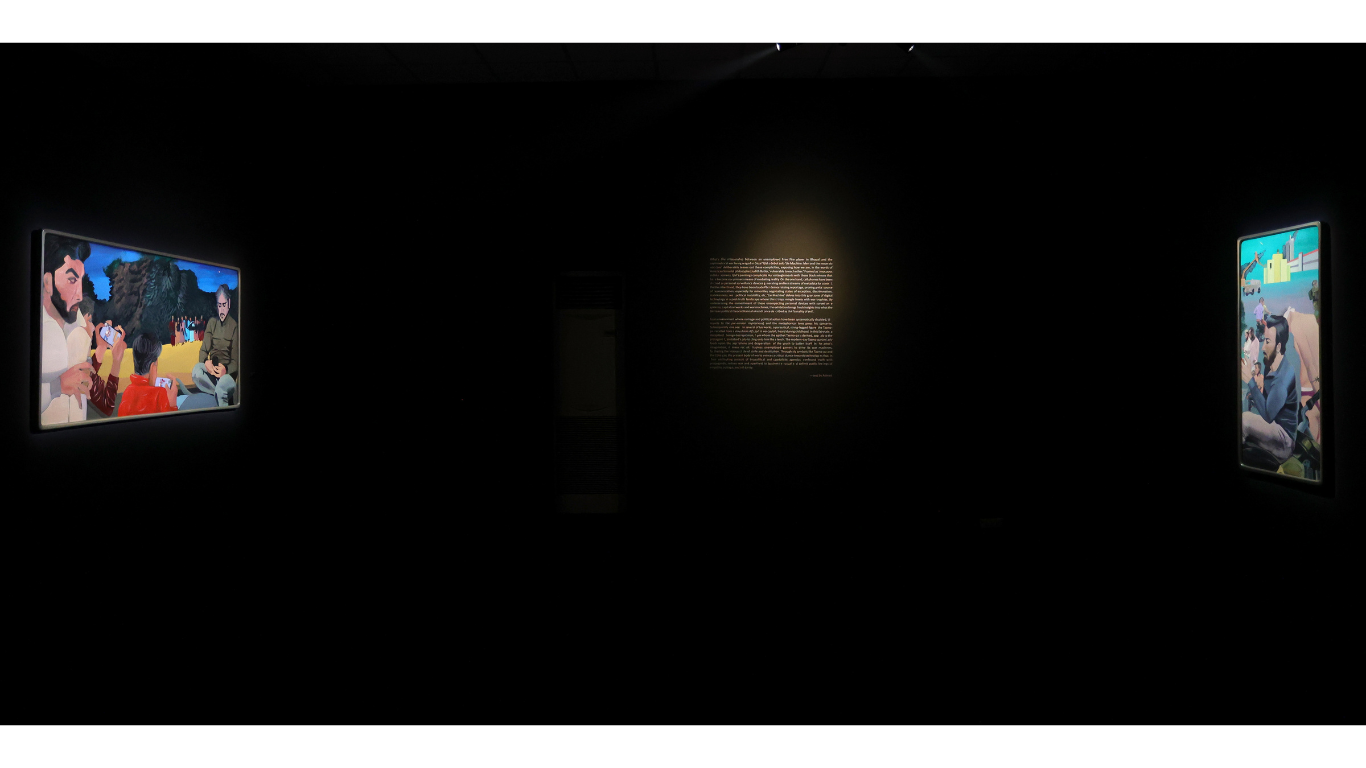

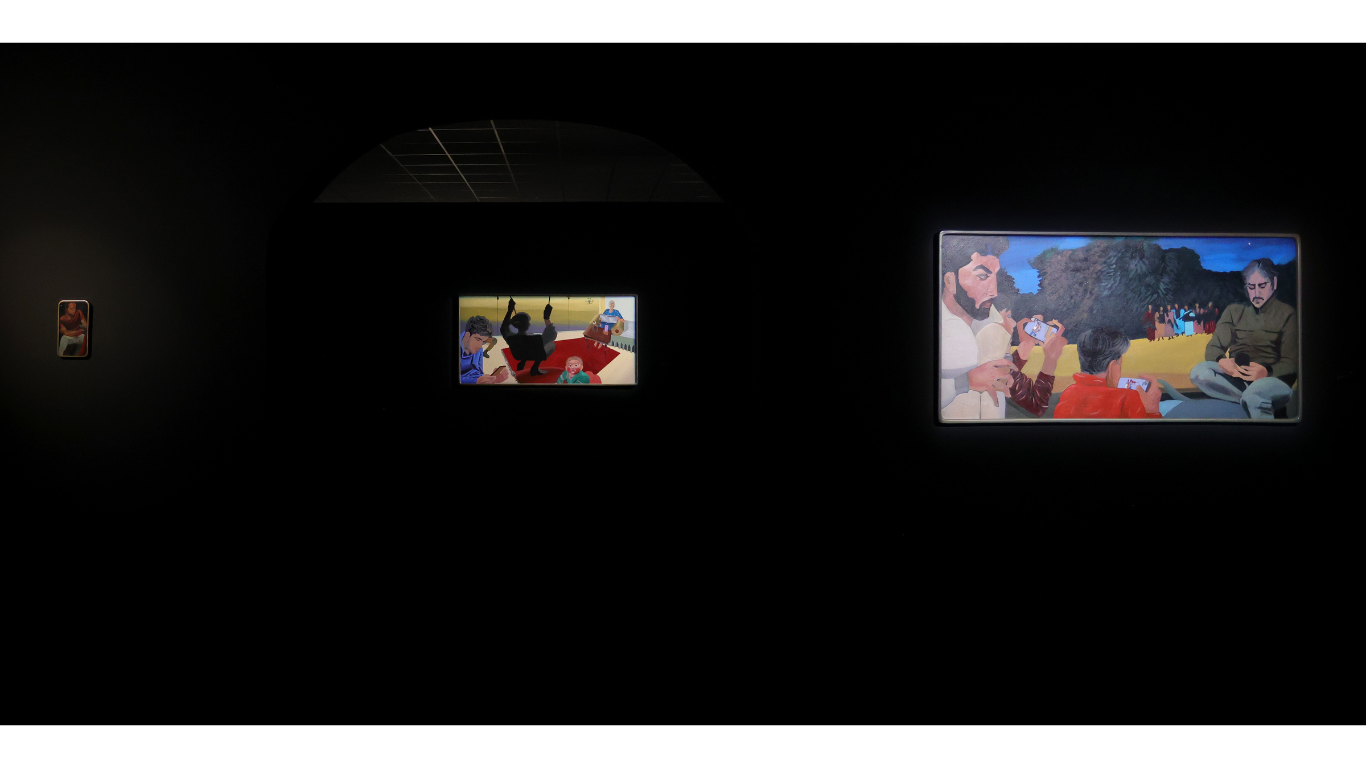

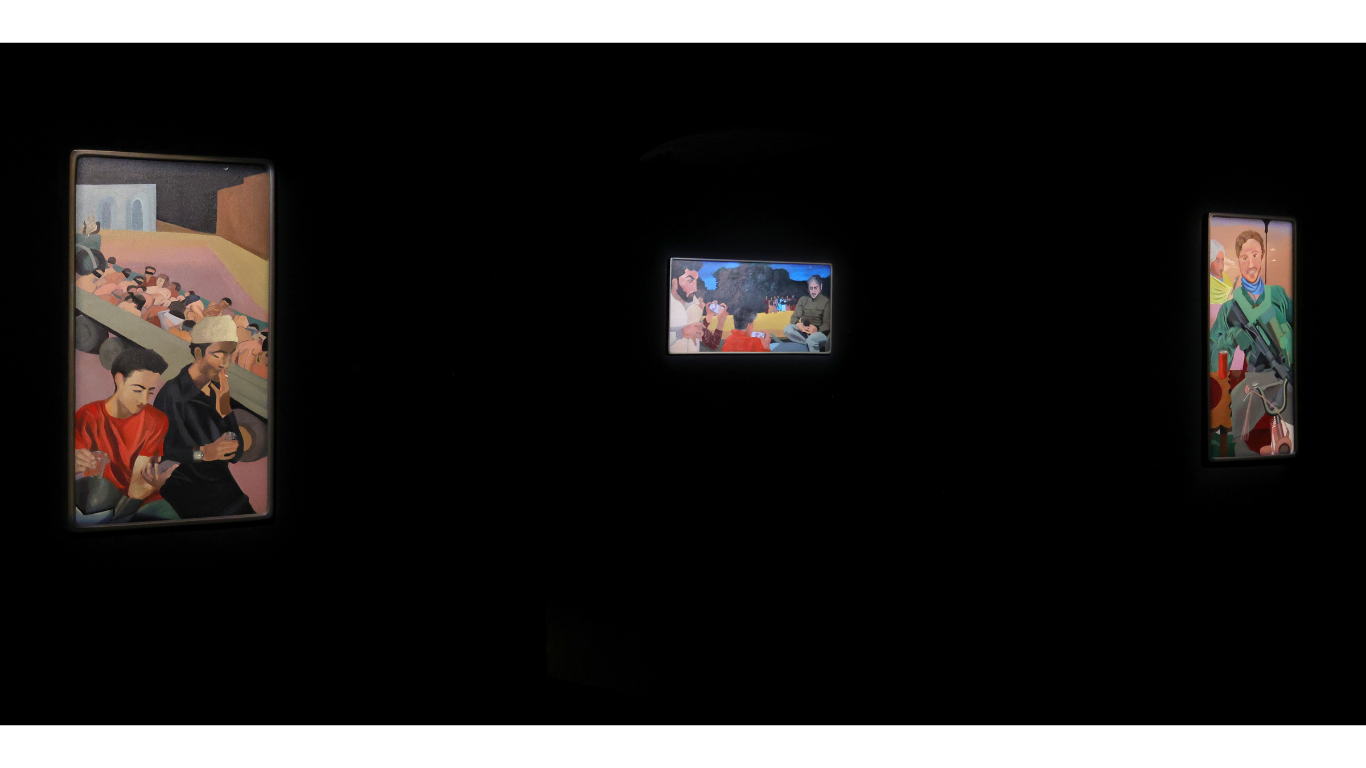

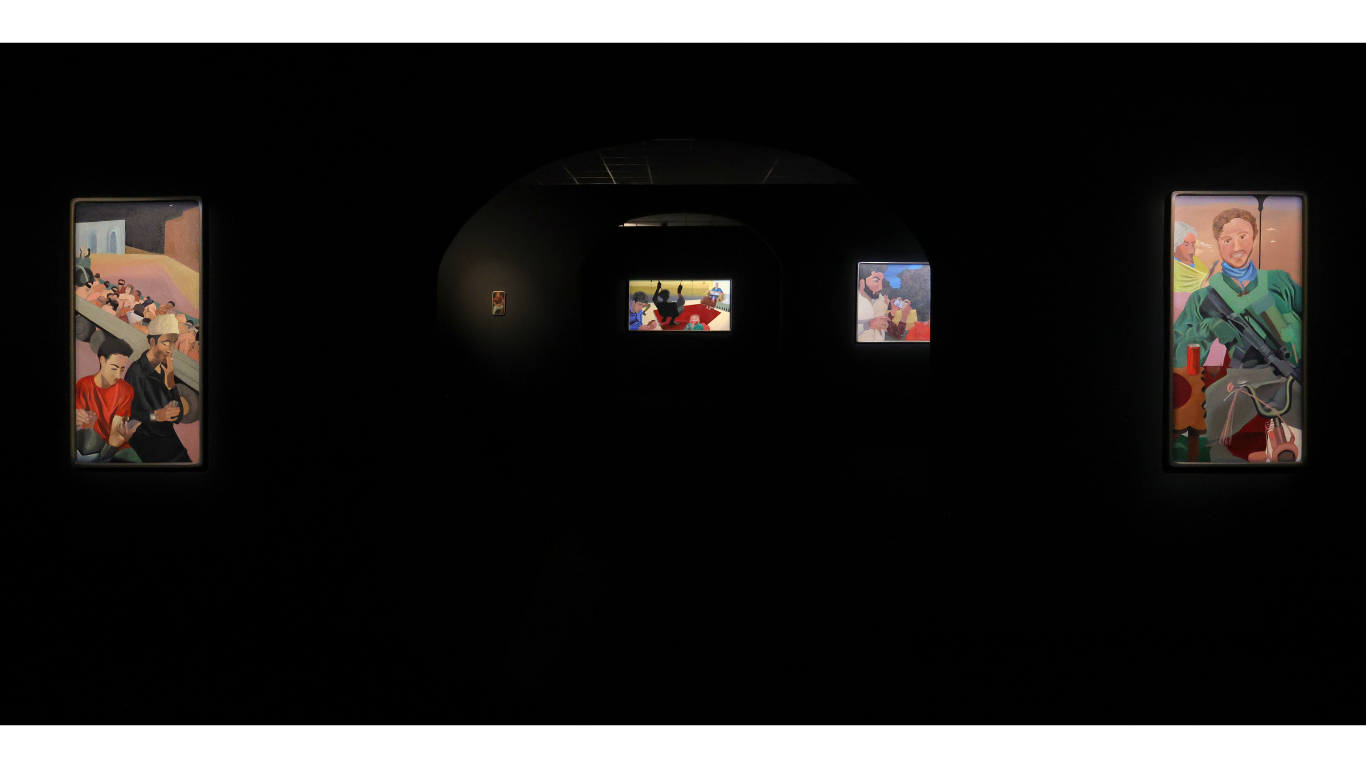

At first glance, the foreground and the background in Moonis Ijlal’s paintings appear to be at odds with each other. While the former offers vignettes of everyday life in Bhopal—Ijlal’s native city—featuring young men killing time at chai tapris the latter erupts with war. These incongruous realities, signified by the foreground and the background, bleed into each other, much as our cell phones bleed over our couches. The schematics of domesticity and desolation are inverted, as the lines between warzone and safe zone are blurred. In one of the frames, a soldier, astride a toy bicycle, jauntily poses for a selfie. Elsewhere, a dog is seen scurrying away with what appears to be a limb torn off a doll (could it be a child?). In fact, this seemingly surreal blending of antithetical states is not as far-fetched or fantastical as one might imagine.

The war is in our midst. It is no longer something that can be safely consigned to the battlefield from where it is sparingly beamed into our living rooms. We’re deeply implicated in its machinations even when we may believe ourselves free from its mandibles. Indeed, in the world that we live in, occupation and domesticity go hand in hand, entwined, as it were, by fibre optic cables. Today, our cell phones not only bring us tidings of disaster from far afield but they can also bring down incrimination in the form of evidence planted through spyware such as Pegasus, or worst still, death in the form of a Hellfire missile dispatched from a Predator/Reaper drone. With the advent of disaster capitalism, strife has spilled into our homes. In particular, the growing use of drones and artificial intelligence in state-sanctioned killings has bolstered the feeling of embattled domesticity. And when drones vulture over heads, no one is immune from the line of fire.

What’s the relationship between an unemployed Free Fire player in Bhopal and the asymmetrical war being waged in Gaza? Ijlal’s debut solo ‘Lie Machine: Men and the moon do not care’ deliberately teases out these complicities, exposing how we are, in the words of American feminist philosopher Judith Butler, ‘vulnerable to each other.’ Framed as innocuous cellular screens, Ijlal’s paintings complicate our entanglements with these black mirrors that have become our primary means of mediating reality. On the one hand, cell phones have been decried as personal surveillance devices generating endless streams of metadata for control. On the other hand, they have been lauded for democratising reportage, proving a vital source of representation, especially for minorities negotiating states of exception, discrimination, statelessness, war, political instability, etc. ‘Lie Machine’ delves into this gray zone of digital technology in a post-truth landscape where thirst traps mingle freely with war trophies. By underscoring the enmeshment of these unsuspecting personal devices with surveillance systems, capital networks and war machines, the exhibition brings fresh insights into what the German political theorist Hannah Arendt once described as the ‘banality of evil’.

In an environment where outrage and political action have been systematically disabled, Ijlal resorts to the pur-asraar (mysterious) and the metaphorical to express his concerns. Subsequently, one sees, in several of his works, a parasitical, string-legged figure, the Tasma-pa, recalled from a story from Alf Laylah wa-Laylah, heard during childhood. In this fairytale, a deceptively benign decrepit man, from whom the epithet Tasma-pa is derived, appeals to the protagonist, Sindabad’s pity to cling onto him like a leech. The modern-day Tasma-pa similarly feeds upon the aspirations and desperations of the youth to batten itself. In the artist’s imagination, it mass recruits hapless unemployed gamers to drive its war machines, furthering the vicious circle of strife and destitution. Through sly symbols like Tasma-pa and the Coke can, the present body of works evinces a critical stance towards technologies that, in their unthinking pursuit of biopolitical and capitalistic agendas, confound truth with propaganda, reduce war and apartheid to business-as-usual and delimit public feelings of empathy, outrage, and solidarity.

—text by Adwait

————-

1 This line has been excerpted from a poem titled ‘Pir-e-tasma-e-pa.’ The poem criticises the undermining of science by religious dogma and faced censorship at the time of its publication.

2 See John Naughton, ‘Death by drone strike, dished out by algorithm’ in The Guardian (21 February 2016). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/feb/21/death-from-above-nia-csa-skynet-algorithm-drones-pakistan (accessed 21 January 2025).

3 See Judith Butler, Vulnerability in Resistance (Duke University press: USA, 2016).

4 See Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (Penguin Books: New York, 1976, c.1964).